A couple of days back, my friend K.B.Vinod, a good reader, had come to meet me at my office. He is in the software industry. We got talking about my difficulties with making railway ticket reservations. Vinod suggested that I make the reservations online. But I would need a credit card for that, I said. “What? You don’t have a credit card?” Vinod was surprised. “Okay, never mind. Get a debit card instead. The bank will issue one.” “But you need to have money in the bank for that,” I said. He was struck speechless. It can sometimes be very hard to describe to software engineers how the rest of us mortals get by.

When I had applied for a Canadian visa at the embassy in Delhi, the red-haired lady who scrutinised my application during the interview could not believe the numbers on my annual income certificate and monthly salary slip. “How does one live on this?” she asked. “I am alive and before you. Is that not proof enough?” I asked. She laughed but refused to issue the visa. Then I applied again with the support of Mr. M.K.Santhanam, the Assistant Director of the Department of Publication, Government of India. I had to submit extensive pieces of evidence to demonstrate that I was, indeed, a real, great writer. It was all very delightful.

Vinod looked around my office. “A fine room. Uncomplicated work. I’m jealous of you…” he said. His job sounded like getting squelched every day between two elephants. I was terrified just hearing about it.

I chose my present job deliberately. If not for this job, I could not have written as much as I have. Twenty-three years ago, when I qualified for the position and went in for my training as a telephone assistant, the trainer explained my duties. He had had sixteen years of experience as a telephone assistant, had subsequently been promoted to manager, and now, in his grey years, he was staying on as a trainer. “This is a very simple job,” he said. “You can train a chimpanzee to do it.” My classmate, Thomas Cheriyan, put his hand up. “So in sixteen years, would it also grow to be a trainer, sir?” he asked.

The same job, for twenty three years. Over and over. I can finish it in a flash without any effort from the mind or intellect. At least a few of the people who come in every day from the villages nearby are interesting to observe. I can leave at the end of the day without any particular burden on my mind. I can simply be another nondescript employee at work.

Many people may have noticed this. There will be a few individuals at our workplace who have been employed there for a very long time. At times we may recognise them, but most of the time we are not aware of their existence at all. Such people are in a very safe position. If you ask for me at my office, half the employees may not even know my name. People don’t think about me unless there is a memo to be answered, a form to be filled out, or a meeting at the union.

So, in summary, no regrets. I never had a need for great amounts of money. My friends will believe me if I say that at no point in my life have I felt any lack of money. Whatever I had was enough. Even when I was a traveller, the money I got by doing small jobs here and there was sufficient for my needs. In those days, it was easy to get a proofreading job at the presses.

Twenty years ago, I made the decision that I would not seek to get promoted at work. It was almost a condition that I laid when I got married to my wife Arunmozhi. I will not make an effort to improve my financial status any more, whatever I make is more than enough for me, I said. She immediately agreed, but that’s not the great thing. The great thing is that her opinion has never changed since.

Clothes, food, comforts—whatever I had was enough for me, I never had greater aspirations. I think I can confidently say that there is not much in my material life that I truly desire to possess. I question myself from time to time if that is really so. Every day I get a small amount from Arunmozhi for my daily expenses, and at the end of the day I always have some money left over. I turn myself completely against all indulgences, including drink and smoke.

After I had attained this understanding, I made it a rule for myself. In 1988, a Malayalam news outlet wanted to branch out into Tamil. They asked if I was interested in becoming its editor. At that time, I was a temporary daily worker in the Department of Telecommunications. I was offered a salary twelve times more than I made then. There would also be other comforts, honours, the benefits of a network.

It is true that I was tempted. I asked for advice from a writer I had regard for. “It is a good thing to become a journalist in a material sense, true. But as a writer, it will be your end. There is no journalist in India who has also evolved into a good writer. A man who uses language mechanically all day will lose the ability to hone his own inner language. The Indian journalist has no freedom of thought. He is bound by the directives of his employer, and spends most of his day in frenzied occupation. I know many who are decaying in such positions,” he said.

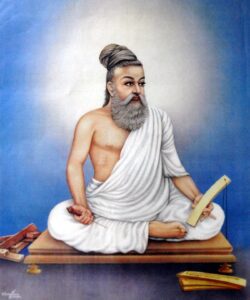

I could not make a decision for a week. The mind plays tricks on you: I started resenting that writer. I came up with all kinds of reasons to justify my hatred for the man. It was simply a way to ignore his advice. But I was filled with hesitation. I could not commit to accepting the position either. It was then, that I happened to turn the pages of the Kural at random. One of them caught my eye, and has stayed with me since.

Yaadhenin yaadhenin neengiyaan nOdhal

Adhanin adhanin ilan (Ku. 341)

Whatever, whatever, if renounced, the suffering

From that, from that, will cease.

I did not get its full import then. But it was an answer. Refusing the offer would be the greatest freedom, I realised. I said no. Saying ‘ o’ is momentary act. But really, it is only after we have crossed that moment that we truly gain conviction. Now, when I think back on it, I am only filled with joy. Saying ’no’ has has only given me greater freedom and contentment.

I have repeated that Kural in my head like a mantra many, many times. At many crossroads of my life. At one point, the word ’suffering’ withered from my memory. The Kural still remains mine, but with a small difference:

Whatever, whatever, renounced

That, that, is no more

Parimelazhagar, in his commentary on the Kural, provides another shade of meaning. Renouncing the world, one thing at a time, leads to liberation. But every little renunciation, to that extent, affords a little freedom.

This understanding is an expansion of the wisdom that Buddhism and Jainism have revealed. Buddhism calls this desire, this thirst for life, trishna. When a man lets go of even a single bit of this desire, to that extent he is freed from it. Letting go of all desires [uppekha] leads to ultimate liberation. The mind that is caught in the mires of worldly life cannot know the truth. It can only see everything in the light of its own fears and desires and needs. That is a conditional, circumscribed knowledge. Only a truly free mind can see the whole truth. Later, these ideas were also influential in Hindu spiritual traditions.

Even without entering into philosophical deliberations about the ultimate truth, I was able to see the truth of this statement when applied to my own life. First, we need to take the literary form of the Kural into account. A Kural is not a song or a verse, they can more aptly be called sutras. All the great literary works of the past which hold the status of the canonical text in various traditions have such a form, where they present their ideas in a highly condensed manner. The Kural, the Gita, the Brahmasutras, and the Thirumandhiram are all examples. They are not meant to be simply read and interpreted. Rather, they need to be impressed word for word in the mind, and then repeated and deliberated upon constantly. Each of them is a kind of mantra for meditation and reflection.

As we dwell upon the words in a Kural over and over throughout our life, we find that they resonate with events in our own life, and thus attain a special personal meaning. Sometimes we see people interpret the Kural in their own special way. There is an endless wisdom in the words of the Kural. The reader should arrive at an experiential meaning of the words through the course of their own lives. It is only by this journey of personal discovery that we truly understand the Kural. Only then does the Kural help us.

The verbal structure of this Kural brings the image of a big marketplace to my mind. We enter, and walk past each stall. As we cross each stall, we disregard its offerings. “No, thank you,” we say, at each stall. To that extent, our burden is light. To that extent, we are free. “Whatever, whatever – from that, from that” – that rapid phrase evokes this image of continuous refusal, release and progress.

Everything that we desire takes up our freedom to that extent. This is not knowledge meant for renunciates alone. I have felt repeatedly that this idea has enormous meaning, even in one’s everyday family and material life. Only the currency of freedom is valid in this market.

Our freedom is the basis of our joy. That is always the yardstick. A house that is filled with fewer things offers more space to move about, run around, and stretch out.

I understand that it is impractical to renounce everything entirely when we have our worldly lives to contend with. The desire and will for attainment is necessary for accomplishment. It is in accomplishment that we can truly realise our latent potentials and be personally satisfied. It is best to want and pursue what our inner nature unquestionably wants. It is necessary to strive and achieve the best possible expression of our inherent nature. Our duties are necessary. Our responsibilities, as a member of our families, our societies, is also necessary. The little delights of our life, even those are necessary.

However, to attain even what is necessary for us, the strength to say ’no’ is essential. If we are propelled by the unstoppable force of our needs and wants, we keep losing. The ability to say ’no’ is the basis of freedom. It is the only strength on whose back that can establish our true nature.

[The Kural, Chapter 35, Renunciation, Kural 341]

Translated By Suchitra Ramachandran