Gandhi is often accused as behaving like a Baniya. In Tamil Nadu, it alleged that Indian Nationalism is dominated by the “Brahmin-Baniya ”, a sly reference to Gandhi. What do you think? Did Gandhi show his Baniya attitude in politics?

Sivaram Soundararajan

Dear Sivaram,

Of late, nothing else in my website is read with so much excitement as the articles on Gandhi. Letters are pouring in and I am writing this as one long reply to all of them.

As you have asked, ‘Was a Baniya’s attitude apparent in Gandhi’s actions?’ Yes indeed, his approach was that of a Baniya. The answer to the second question is also the same. Who, other than an immensely successful senior Baniya, could be a better guide in your business?

I would not acknowledge those who abuse Gandhi as a Baniya, as most of them are casteists. They cannot shed their caste identity and the communalist view even slightly. They believe that caste identity is inseparable and hence, whenever someone has to be discredited or abused, they start with targeting his/her caste identity. Such people do not even have the decency to qualify to take part in any debate about Gandhi.

If you are interested in making an honest assessment, we may ponder over certain facts. What are the positive and negative effects of one’s caste on his/her personality? Does the caste system contribute anything to the society? What is the background of Baniya tradition in Indian history?

A child is engulfed by its caste, the moment it is born. There is no place in this debate for the age old rhetoric that describes caste as a system thrust upon a group of people by another group just as a tool for suppression. It has no backing of sociological research. In the Indian society, caste system evolved from its early tribal identity and with the emergence of feudalism, it took the shape of hierarchical power structure.

For the billions of Indians, their caste is an important cultural aspect that determines their personal identity. Irrespective of the position of their caste in the social hierarchy, this identity forms part of their tradition and they are proud of it. This makes them refuse to part with their caste identity. They live and work together as a group of their caste.

In our country, caste and one’s profession are entwined. Every caste has its own profession. By functioning together as ethnic groups for ages, they have acquired certain special skills and unique qualities. The group that has been into wars for three thousand years acquired one set of skills and the caste that has been involved in trade for generations acquired a different set of qualities.

Lessons learnt through the experience of the forefathers are nurtured within that caste through its social arrangements, orthodox practices, beliefs and traditions. This gradually cultivates the mindset to suit these arrangements and then this attitude gets evolved into the collective characteristics of that caste. This gets embedded in the language, festivals and the like of that particular caste in the form of imagery. The child that is born into such an environment grows naturally absorbing these attitudes in its subconscious.

The individual personality of that child may grow in different directions. A conservative would say that one can think only within his caste and that there is no personality for an individual. A fascist would make it a rule. However, to think that it is possible to look at a man after completely detaching him from his traditional identity would only be wishful thinking. The personality of a man is determined by the dialectics between these two factors.

For example, I am a Nair, a clan of soldiers and landlords. Throughout my life, I have been trying to come out of the caste identity. Caste has no role in my personal or social life. Four hundred years ago, my caste had entered into the folds of classical arts and literature and reached the cultural heights of a feudalistic tradition. A hundred years ago, the Missionaries had introduced modern education to my caste.

Nairs are not a strong ethnic group anymore. Most of the Nair families have sons-in-law, daughters-in-law and grandchildren of various castes as a result of inter-caste marriages. Of late, marriages between the white and yellow clans are solemnized. To Nairs, the status that comes through money is the yardstick but still, their unique traits continue to exist.

The ‘caste attitude’ is a reality and it need not be looked upon from an entirely negative perspective. It can be said that skills acquired over centuries become traditional nature. Certainly, some of these attitudes are desirable and some are not. No single caste can take credit for all virtues nor can it be held responsible for all vices. This has made a positive impact on many professions in India, especially that of smiths and sculptors.

But I think there is no value today for many of the qualities traditionally acquired by the warring castes, like mine. Only the useful intuitions that are profession-related have some significance. I think, many attitudes acquired by the Baniya community over centuries might have worked on Gandhi in the form of beliefs, practices and intuitions.

Not just in India, but throughout the world, we can see the best among traders have come predominantly from drought-prone areas and deserts. This may be due to the fact that the attitudes acquired by them to survive such harsh conditions have made them successful in trade. This includes attitudes like being thrift, enduring patience, the will to win and functioning as strong close-knit groups.

From time immemorial our best traders have come from Rajasthan and Gujarat. Literature shows us that traders existed in Dwarka from ancient times. Their attitudes were shaped by their trade.

Even to this day, Jainism has a firm stronghold in these areas when compared to the other States. In India, Jainism evolved 2500 years ago and its fundamental vision evolved from lokayata [atheistic and materialistic] tradition that already existed. So, in essence, Jainism is quite against the orthodoxy which was the mainstream Indian spiritual tradition.

We can briefly sum it up like this: the wisdom of the Vedas, which is the mainstream of Hindu tradition, believes that this universe possesses an unknown central objective or a central plan or a force. It argues that this centre is the only Truth and all that we see are different illusions of the same. It defines the essence of the Universe as the Brahmam. All that we see are various forms of that Brahmam.

The Vedic wisdom’s idea of liberation emerged from this. It says that while we indulge in worldly activities, we also need to be aware that everything is an illusion. This detachment would help one perform one’s task in the best possible manner. In the end, when this illusion completely disappears and when one identifies the self with the essential truth, it becomes liberation – the salvation that the Vedic wisdom refers to.

There were many ancient visions that opposed this central idea. Jainism emerged by absorbing the essence of these various perspectives, formulating an extensive philosophical base. Its view of the world is called Sarvaasthivaatham. It means all that we perceive in this universe are true and nothing is illusory or falsehood. So, to search for the essence of this world one need not go outside the world.

As an extension to this, the Jains formed the idea of Sarvaathmavaatham. Everything in the Universe, be it a living being or an inanimate object, has a soul. To Jains, soul means the essence of thought. A stone remains a stone because of its soul. That is to say, we are one of the billions of souls in this universe, like the dog, the plant, the bacterium, the mountain and the pebble and nothing beyond that.

From this, the Jains arrived at the fundamental vision called Anekaanthavatham. Its essence is that the truth man perceives, whether at the simpler level or higher level, will always be in a plural form. Never will a man’s mind come across the absolute universal truth. Man is so small and the truth is so magnificent.

There will always be many sides and angles to the same truth. Everything is true; at the same time, everything is false. Complete truth can be realized by us only as a whole of hundreds of billions of truths. To explain this with a simile the Jains told the story of five blind men and the elephant.

Gandhi was fascinated by this pluralism. “Plurality of truth is an attractive idea to me. It is with this theory that I understand a Muslim or a Christian through his own perception. Initially I had lost my patience, because of the ignorance of my opponents. Now, I am able to love them, because, now, I can perceive myself from their angle. My pluralism emerged from the twin principle of truth and non-violence”, said Gandhi.

Chiyathvaatham, the next primary principle of the Jains, emerged as an extension of this. No knowledge that we gain about our environment is complete. This is close to skepticism of the ancient Greeks and the modern physical theory that ‘Nothing is absolute and everything is relative’.

Jainism defines worldly life on the basis of these four visions about the Universe. This world is true. The sorrows and pleasures of it are also true. Everything in it has essence and its own existence. The essence and purpose can never be completely understood by us. Thus, completeness means living the life that has been given to us in such a way that our soul becomes satiated.

Ahimsa is the first rule for such a life. When every living being and every inanimate object has a soul, non-destruction of others becomes the highest value. A true life lies in maintaining the best relationship with every other soul. This is called Ahimsa.

Ahimsa makes one to be true to everything that is related to him. It makes one compassionate towards everything. After establishing one’s life, it helps one reach the stage where nothing more is needed. Axioms like compassion and renunciation are the practical stages of Ahimsa. One who leads such a life is considered worthy of his living. He is the one who attains godliness. This is the wholesome-stage or self-realization (mukti) propagated by Jainism. Almost all these principles can be found in Tirukkural.

The wisdom of the Vedas appealed to the Brahmins and the Kshatriyas. In the early times, they were the main forces that consolidated and retained the social structure. The central idea called ‘Brahmam’ was like the thread in a garland used to link the religions and practices of different ethnic groups, to bind them as a single social structure and to establish feudal governance by arranging them vertically. The Hindu religion and the earlier monarchies were a result of this.

In the next stage of Indian social formation, the contribution made by the Vysyas was significant. Land and sea routes were discovered throughout India. They were like the network of nerves that linked the vast regions of India. Traders who travelled through them started to connect between each other thousands of societies that were in different stages of social development. This is how the India that we know of was formed some 2500 years ago.

In the course of establishing such connections, the traders slowly emerged as the dominant force. Researchers call this the rise of the trade power against the Brahmin-Kshatriya dominance. With their wealth, traders obtained more authority. Since then the dialectics between the Vysyas and the Brahmin-Kshatriyas continued in our society for nearly a thousand years.

Chanakya, in his ‘Artha Sastra’, delineates how the King should keep the traders under his rein. We can understand how the traders were involved in the power games from the plays like Mudra Rakshasam. Ancient scripts like Kathacharita Sagaram speak mainly of the dominance and wealth of the traders.

In the course of this evolution, a religion was required for traders, a religion that would conduct the social dialogue, instead of creating layers of authority, a religion that would bring thousands of social groups in different strata within the ambit of some common values, and a religion that would not believe in the power of weapon but would give an equally powerful weapon. Thus, Jainism became the religion of traders. Three hundred years later, Buddhism too emerged in the same way.

Jainism spread throughout India with the support of big traders. It was the first ‘missionary’ religion of the world. Dedicated religious preachers were sent out in all directions, with specific plans. They slowly mingled with the life and traditions prevailing in that place and established their ideas there. As the financial assistance from traders established a big base for the spread of Jainism, it engulfed India rapidly.

Like the imprints of a water course, we can still see the path of the spread of Jainism in the Central part of India. From Rajasthan to Gujarat, via Ahmedabad, it entered Madya Pradesh, through Bhopal into Andhra, through Rayalaseema into Karnataka, via Shravanabelagola it entered Tamil Nadu and reached upto Chitharal in Kanyakumari. Even today, important religious seats of power of Jainism are lined up in these places. At the same time, another important sea route of trade between Thanjavur and Bengal remained unaffected by Jainism.

Education and medicine were the chosen weapons of Jainism. Jains have written grammar and moral treatises in all Indian languages, including Tamil. They were the ones who took Ayurveda throughout the country. Through the Dharamshalas which provided education and medicine, they reached out to common people and greatly influenced them.

Traders supported Jainism since it spread values that were favourable to trade. One can easily guess how the Indian landmass might have been at that time. Thousands of tribes might have been relentlessly fighting each other. Jainism created an excellent amicable atmosphere among them. Its non-violence might have been a great blessing for a land where war was a way of life. They combined Ahimsa with education. They propagated Sanskrit as a common language throughout India. They paved the way for interactions between the tribal dialects and ancient languages through Sanskrit.

One could say that the overall Indian cultural structure was formed by the Jains through compromise and dialogue. The religion of the Vedas was already widespread in India. It had linked thousands of tribes through Puranas and had built a power structure by arranging them hierarchically, based on the authority they had. But, within that structure, every unit was always fighting with each other. Naturally, Jainism, which replaced war with compromise and dialogue, through education, became the favourite religion of the rulers.

Buddhism succeeded Jainism in a similar fashion. Our tradition had regarded both as one religion. Their contribution to the Indian society through their culture and thought for centuries is significant. Both are religions of the traders. All of the Indian trader castes belonged either to Jainism or Buddhism.

Some historians say, Jain dominance lost its strength due to the emergence of Bhakti movement. They were absorbed by the Bhakti movement. It would only be proper to say that the essential axioms were further developed. The people who were Jains were the ones who established the Bhakti movement too.

If Jainism and Buddhism can be considered the religions of the traders, then the Bhakti movement can be considered the religion of Sudras. The vedic religion of the Brahmin-Kshatriyas is based on rituals (yagna) and philosophical thoughts. Jainism and Buddhism of the traders are based on renunciation, philosophical thoughts and meditation. Bhakti movement of the Sudras is based on temple festivals and arts.

Bhakti Movement adopted compromise and Ahimsa, which were the basic tenets of Jainism and Buddhism. Though it did not nurture the complicated philosophical rules of Jainism, ideologies like Anekaanthavaadam were deeply embedded in the Bhakti Movement. Most of the sages of the Bhakti Movement had the amicability of respecting all view points.

From Tamil Nadu the Bhakti Movement spread to the North for centuries and took entire North India into its fold. The wave of the Bhakti Movement lasted up until Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. Since arts were the media of the Bhakti Movement, Vaishnavism outdid Saivism. Most of North India took to Vaishnavism.

From the many rituals and practices of the trader communities of Tamil Nadu like Naattukottai Chettiars, Saiva Velalars and Saiva Mudaliars, we can infer that they were Jains before the Bhakti Movement and later embraced Saivism. Even in the seventeenth century, some of the Chettiars remained Jains. When most of North India embraced Vaishnavism, one set of people continued to be Jains.

Even today, Jains in India are the prominent group of traders. Jainism has advocated charity as the integral part of their trade. Most of the charitable institutions in India were established and are maintained by the Jains. In Tamil Nadu, most of the major charitable trusts belong to the Chettiars. The bitterness that the common people have towards the traders in other cultures is absent here because of this benevolent attitude.

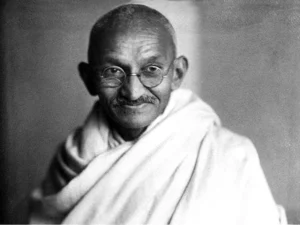

Gandhi belonged to the trader’s community which embraced Vaishnavism. The word Baniya is the contraction of the Sanskrit word ‘Vaanijya’ (Baanijya-Baaniya-Baniya). It is the sanskritised form of the Tamil word ‘Vanigan’. Within the common caste identity of Baniya in Gurajat, Gandhi belongs to the sub-sect called ‘Modh’. This sect worships Mother Modheswari, a mother god with eighteen hands. The area where these people lived was called Modhera. From this came their caste name. There are Brahmins, Vysyas and Sudras within the Modhis. We may call Gandhi a ‘Modh Baniya’.

It should be noted here that a group of people, while adhering to Jainism, can still worship other Gods such as their family deities. Worship of family deity was prevalent in Tamil Nadu, when Jainism ruled the roost here. It is similar to our worshipping Madasamy and Shiva simultaneously. Modhi Baniyas were mostly Jains until the seventeenth century. Their Jain Mutt is situated in Dhandhuka near Ahmedabad. There are 500 Jain temples, built by Modh Baniyas in the place called Wadhwan.

Though Gandhi’s family embraced Vaishnavism, they continued to be Jains. This should not be compared with conversion to Islam and Christianity. For nearly three hundred years after Jainism became weak and Saivism and Vaishnavism had become strong through Bhakti Movement, billions of people continued to follow Jainism and Saivism/Vaishnavism simultaneously while still worshipping family deities. Gandhi’s family had been following Jain practices. Gandhi’s mother Puthlibai worshiped the Jain sage Besari Swami as her Guru. In his book ‘My Experiments with Truth’, Gandhi says that Puthlibai made him promise to stick to vegetarianism and other orthodox practices when he left for London, as advised by the Swami.

So, we have to consider Gandhi as a Jain too. In many contexts, he talks about his belief in Jain practices. Gandhi was a contemporary extension of the Jainist ideology that united India. The Ahimsa that he advocated was the basic tenet of Jainism. Gandhian ways of struggle like Satyagraha and fasting were being successfully practiced by the Jain sages for many centuries.

When we look at the Indian history, we can observe two trends in the unification of India. One is the Brahmin-Kshatriya way. It creates a centre, undertakes extensive dialogue with all sections, undergoes change and accommodates everyone within its flexible structure. It creates a hierarchy where one group is placed under another. Simultaneous use of wisdom and weapon is its modus operandi.

The second is the way of Jains-Buddhists. It creates a compromise based on a central objective, where everyone can take part. It mobilizes people through Ahimsa. The way of the Bhakti Movement is the same, but of a different form.

We can see that the way advocated by Tilak, Aurobindo and the like is that of Brahmin-Kshatriyas. Tilak has written extensively about this. It was the only possible way that was known to everyone then. Against this was the method of European Parliamentarian politics, put forth by Gokhale. It had no origin in Indian tradition. So, it did not take root here.

We can see this in the verses of Bharati too. In his poems like ‘Shivaji’s address to his Army’ and ‘Panchali Sabatham’ he praises the valour of the Kshatriyas. He relates Arjuna’s valour to modern India and says, ‘Explain with the eyes like that of Arjuna’. It was an idea that elated the mind then and it was considered the only way.

Gandhi brought into politics the second way, which was prevalent in the Indian tradition, but had been completely forgotten until then. It was the way of the Jains. Tilak and Aurobindo were Brahmin-Kshatriyas and Gandhi was a Baniya. He was an extension of the great trade culture that united India in the Ahimsa way. He was an ideal mixture of Jain-Buddhist culture and the Bhakti Movement. Behind him was a great tradition that had Ahimsa, education and medicine as its principles.

2

Lloyd Rudolph and Susanne Hoeber Rudolph, in an essay titled ‘Fear of Cowardice’ (Postmodern Gandhi and other Essays) speak extensively about how courage and cowardice were traditionally imbibed in the psyche of various Indian castes and Gandhi’s contribution towards this.

British administrators, who worked in India, documented their observations to be used by their successors. These have become important historic archives. J.M. Nelson, who wrote ‘The Madura Country – A Manual’, attributes the characteristics of the people of Tamil Nadu to their castes.

“The pharisaical Brahman, the lawless Maravan, the mean Chetti, the selfish Vellalan, the dull Nayakkan, the skulking Kallan, anxious Kuravan, the licentious Pariah, these and a score of other castes are distinguishable each by peculiar traits of character and modes of conduct”

Though this is based on his sarcastic views about the Indians, it shows how the British analysed things.

Whatever might be the intention of these records, we get a glimpse of the various traits within the Indian society at large. Over the centuries, it has been established that each caste should practice a specific profession and the qualities of the castes were related to their professions. In Indian society, some castes were involved in warfare and their main attribute was fighting spirit. Similarly, some other castes with tribal instincts also had the inherent quality of fighting.

In general, many of the Indians were non-violent and had a conciliatory attitude. This was due to the fact that the Indian characteristic was determined by Jainism. All of our art, literature and culture emerged from exchange of ideas over a long period in a peaceful environment. Waves of foreign invasions that plundered this society since the tenth century had completely destroyed its military establishments and wiped out its self-confidence and valour. The then British rulers considered the average Indian to be submissive.

The Rudolphs quote the then judges like James Fitzjames Stephen and the administrators like Lord Curzon, segregating the Indian society into masculine and feminine societies. India had more feminine societies and they were predominantly involved in trade and services.

The British patronized the Muslims and the Sikhs whom they considered masculine societies. In Tamil Nadu they repressed many of the masculine societies like the Thevars through the Criminal Tribes Act (CTA), 1871 and managed to bring the entire landmass of India under their control.

It is interesting to note that they classified the entire European society as masculine and Eastern societies as feminine. They considered the Eastern Society as stagnant and inefficient.

By the time the freedom struggle started the power of the Kshatriyas had worn out. Since their entry in India, the British won over them in hundreds of battles. The final blow came with the freedom revolt of 1857, which was thwarted completely due to internal contradiction.

From the early times of Indian Renaissance, rejuvenating the Kshatriyan valour was repeatedly envisaged. The Rudolphs point out how Vivekananda made a clarion call to the strong and healthy youth. Tilak took this call further, tried to mobilise the power of the Kshatriyas and wage a war against the British.

This remained just an idealistic attempt without making any noticeable impact. It could not progress beyond isolated acts of terrorism, in fact, it was mostly confined to Bengal. This approach could not have been used in any form or manner in India. Wherever it was tried, the results were pathetic.

A classic example was the Nellai uprising. Today, when we read about the arrangements made for the armed revolt initiated by VOC, Subramania Siva, Neelakanda Brahmachari et al, we have to conclude that they had little grasp of the concept of armed revolt. Their arms training and combat formation were utterly amateurish, done with immature idealism. The best they could manage was to kill the Collector of Tirunelveli, Robert Ashe.

This armed revolution was envisaged mostly by the middle class Brahmins. They tried to behave like Kshatriyas. They anticipated that the Kshatriya Maravars in the Tirunelveli area would come charging, on hearing their call. Nothing to that effect happened and the British government crushed the Nellai Revolt like squashing a mosquito, with minimal military force. From then until Independence, no freedom struggle of any sort emerged in Nellai.

What went wrong? Those Brahmins did not realise that a century had passed since the valour of the Indian Kshatriyas had expired. They did not understand that the valour of the Kshatriyas were not relevant in a modern political struggle and that changes can occur only when billions of people who had kept away from politics for centuries are politicized and came forward to fight for their rights. They were still living in the times of Arjuna, Shivaji and Gurugobind Singh (great Kshatriya heroes).

Many parts of India witnessed such sundry revolts. They were useful in widespread promotion of the concept of ‘Nation’ among the people. The campaign value of such revolts were enormous but, had they not been suppressed immediately and were allowed to continue they would have ended in disaster. The best example is the 1921 Mopla Revolt of Kerala.

There were two reasons. Firstly, during that period, the British had the best army in the world. It was technologically a superior army of an empire that had seen industrial revolution. Unlimited resources throughout the world were within their reach.

Only an army with a similar technological proficiency could have faced the British army. Even then no one could defeat the British, because it neutralised the challenges from similar technically advanced countries by entering into various military agreements and treaties.

Secondly, the British ruled India with the approval of civil societies made up of billions of people. When the British came to India, the existing Governments here were feudalistic. The British proposed a Capitalist Government, as an alternative. Capitalism has much advanced judicial and administrative systems than that of the feudalistic structure. Moreover, when the British came, the empires here had split into hundreds of smaller states that were fighting with each other and existed in a state of anarchy.

Thus, the people here supported the British and it is with that support the British ruled this country. The great British Army had in its ranks loyal Indian soldiers. It was a battalion of Gorkhas, one of the great Indian Kshatriyan powers, that gunned down Indian public under the command of General Dyre in Jalian Wallabagh. The massive administrative structure of the British government was made up of Indians.

Hypothetically ,say let us consider , as dreamt by Tilak, the power of the Kshatriyas had risen and defeated the British government, what kind of a government would it have formed? A small minority of people would have started controlling the entire Indian society. Again a feudal government would have come to power. To attain democracy, where everyone has power, another uprising and struggle would have been required.

Gandhi entered politics at this historic juncture. The structural weakness of Congress at the time of Gandhi’s entry should be viewed in this background. Only two sets of people were into politics then. The upper class people, who believed in the European Parliamentary System and the traditionalists, who wanted to save India’s Brahmin-Kshatriya tradition. Both were minorities. The remaining majority kept out of politics with their typical reluctance.

Martin Burgess Green, in his book ‘The Origins of Non-violence: Tolstoy and Gandhi in their Historical Settings’, extensively examines the roots of Gandhi’s Ahimsa in the ancient Indian Jain tradition. Green says, throughout history, simple Indian farmers have conveyed their expression of protest to the government by their non-violent methods. He says that their struggle was to register their protest through unity and spiritual strength. This was Gandhi’s starting point.

Gandhi spoke to those common men and women. His maiden speech at the Annual Conference of the Indian National Congress held in 1915 was about this. Gandhi asked, “Where are the common men?” He tried to bring those billions into politics. Only he possessed the weapon required, it was India’s Jain tradition. He put forth it in the name of Ahimsa. This has what became a great democratic power in India , with scores of people participation.

The Rudolph’s quote in their book what Nehru had said about the contribution of Gandhi’s political entry meant to the people of India. “Most of what Gandhi had said were accepted only partly by us. Or, they were entirely rejected. But this is secondary. In essence, what he taught us was fearlessness, truth and the related aptitude for performance. Suddenly it appeared that the dark burden of fear had disappeared from the shoulders of the people. Though not entirely, it disappeared to an astonishing level. That was a psychological change. Almost like a psychiatrist, he went deep into the people’s past, found out the roots of their psychic problems, revealed it to them and freed them from the burden”.

This was Gandhi’s contribution to Indian politics. He nurtured the people of India from cowardice to self-confidence and bravery and brought them into politics. Those people, who were hiding with no voice of their own for centuries, gathered into a tremendous force and challenged the world’s greatest empire. By the standards of Indian cultural tradition, that could have been achieved only by a Jain sage and that happened to be Gandhi.

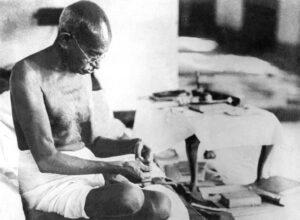

On account of the above the humble ‘Gond’ tribes of India conferred him with the title of ‘Mahatma’. It is the term with which they refer to a Jain sage.From the time he arrived back

to India from South Africa and engaged himself in service to the society that title became associated with him. Later, that title introduced him to the common people all over India. It conveyed to the Indian cultural psyche that, instead of a Kshatriya commanding an army with a drawn out sword, a sage with a peacock feather in his hand has come to guide them.

In 1915, Indian freedom struggle reached its turning point. The stage had come, when Tilak’s faction was about to seize the Congress which was dissatisfied with the course of the Moderates. It was a moment when India was on the verge of joining hands with Tilak, who advocated violent and direct confrontation. At this juncture Gandhi entered politics.

Indian tradition opened up two paths for Indian freedom struggle. One was the Hindu way of the Brahmin-Kshatriyas and the other the Jain way of the Vysyas. The first path was full of Rajo traits that leads to bloody fight. The second path was based on Satva traits that tends towards non-violent struggle. Only brave men can find a place in the former. The latter accommodates only the common people. It was a tradition born out of the Jain culture and transformed into Bhakti Movement. Gandhi is an extension of that tradition. The second path was chosen only because Gandhi entered at the right moment. This helped India to escape from disasters and to survive as a democracy till date. For this, we are indebted to Gandhi.

We can see that almost all of the oppositions that Gandhi faced throughout his life were the result of the contradictions between these two approaches. From the very beginning, Tilak’s faction opposed Gandhi vehemently. Later, the Hindu Maha Sabha alleged that he had chained India to cowardice. The publications of the Hindu Maha Sabha during that period accused Gandhi (in my view rightly so!) of nurturing feminity in the Indian society. This aspect formed the basis for all the differences he later developed with Subash Chandra Bose and other extremist groups.

Even today, Hindu extremists accuse Gandhi of restricting the valour of the Indian Kshatriyas. Refer ‘Eclipse of the Hindu Nation: Gandhi and His Freedom Struggle’ by Radha Rajan. It depicts Gandhi as a British Agent. There are many such books.

They say that the British brought in Gandhi and established him in the Congress when the Indian freedom struggle was at its peak. The reason they attribute is that Gandhi was favourable to the British in the Boer war in South Africa and they thought that his way of fighting would not create violence which might harm the British citizens in India. The moderates weree also blamed of assisting the British in this scheme.

We have to discuss extensively the possibilities of Gandhi’s non-violent ways. It brought within reach, to the millions, a way to fight for their rights by gradually politicising them. It did not push them towards repression through aggressive struggle. Instead, it enthused them with initial victories through various regional agitations. It collected and converted them into a massive force to reckon with and boosted their self-confidence.

Gandhi’s struggle was simultaneously a struggle as well as a self-reform. Gandhian struggles brought millions of people onto a public forum and paved way for mutual dialogue among them, which until then was impossible because of their differences in terms of caste, language, community and religion. This fact is evident in several autobiographies written during that era.

Gandhi’s struggle introduced democracy to Indians. These people who had grown up in a feudalistic set up under monarchy, were taught the basic principles of democracy through the hundreds of institutions like the Harijan Movement, Khadi Movement, Gram Sabha Movement and Ma Sri Sangh Movement formed by the Congress. The autobiographies of TSS Rajan, Kovai Ayyamuthu and K. Santhanam speak about the never ending challenges in building these institutions after reaching out to the people, who were unaware of the democratic values, and educating them about its basics.

Gandhi’s struggles rendered the world’s best army totally useless to the British. Gandhi knew thoroughly the millions of ordinary men who followed him – those who through the wars and anarchies for centuries were slaves and survivors from the destruction of the past. He did not want to make a sacrificial offering of them again for the sake of political change. He ensured that the support of the civil society, which formed the basis for the British rule, gradually diminished and disappeared. Through that he took the nation towards independence and taught that we can attain independence only by strengthening and enhancing ourselves and not by destroying the enemy.

Women’s participation in Gandhi’s struggles was more than that for any other political movement in India. In Gandhi’s days, not even one in thousand women was literate and they never had the right to choose their own life or make their own decisions. Even then they answered his call. Since then ,the participation of women in any other political movement in India is negligible. Gandhi’s movement had a feminine character to it.

One more aspect that Gandhi brought to Indian freedom struggle from the Jain tradition was its ‘missionary’ aspect. He brought into Congress, the Jain practice of sending missionaries throughout India with nothing but poverty, honesty and doctrines as their weapons. He formed a huge army of volunteers who had renounced their family and luxuries, who remained hungry travelling from village to village.

After the Bhakti Movement, which ended with Kabir during the fifteenth century, Gandhi’s volunteer force was the greatest movement that reached out to the common man of India. Actually, it was equivalent to ten Bhakti Movements. In 1921, Gandhi mobilized more members than any other political movement had in the history of the World.They received formal training and an administrative structure was formed to manage them. Nearly three million volunteers went to out to work for the various sections of the Indian society!

Till date, no one has elaborately studied the effects of this great people’s movement in the history of India. What would have been the state of rural Indian society then? There were no popular news media ,very few Indians were literates and even few were aware of anything beyond their profession and their village surroundings. Gandhi’s movement was the first contact that came towards them from the outer world.

Gandhian movement taught them the possibilities of democracy. It showed them that they can collectively fight for their rights. It taught them the elementary lessons in education, handicrafts and health. It told them that there was a society and a country beyond their caste and religion. It politicized the Indians. All movements that came later, including those that rejected Gandhi, were built upon this politicization.

All these were made possible because of the Jain principles that Gandhi put forth, which he has inherited from his Baniya background. India experienced the zenith of Baniya culture through him. Gandhi had emerged into the modern era from a tradition that had united rival tribal groups through compromise and education and had made India a highly civilized society. He was a blessing showered on India by the great compassion of the Tirtankaras.

Hence the fact that Gandhi was a Baniya need not be considered to have a negative connotation. It is our good fortune that a Baniya called Gandhi came to lead this country.

3

3

For a novice trader, the advice of a senior Baniya is always invaluable. Gandhi, the Baniya, was not practicing trade nor did he become a Jain seer. Rather he entered politics through his profession of practising law. Yet the experience and wisdom of the Indian Baniyas, accumulated over a period of two thousand years were subtly inherent in Gandhi and were evident in all his actions.

The Indian National Congress was an institution and it is only natural that an institution would be more successful when it is managed by a Baniya. For any administrator, there are innumerable lessons to be learnt from the way Gandhi guided the Indian National Congress. Only experts in Management would be able to discuss in depth all of Gandhian Management concepts. Many colleges and universities throughout the world teach Gandhian methods of management.

There are many books that are dedicated to this topic but I have read only ‘Gandhian Management’ by Ram Pratap. I understood it fairly well, in spite of the usual management jargon. Even without that a few rules could be grasped just by keenly observing Gandhian struggle.

What could a senior Baniya have told a novice trader? I guess certain fundamental rules as below.

1. Do not burn bridges

This would be the first and foremost Gandhian principle. Never did Gandhi sever his relationship with anyone even after a serious clash or conflict. Congressmen had to face this with distaste many a times. If we take into consideration Gandhi’s beliefs, we can see that there were many situations that should have justifiably forced him to sever his relationship with Md. Ali Jinnah.

It would not have been wrong on his part if he had done that, especially after the Muslim League had created a rift between and hatred among the Hindus and the Muslims and unleashed violence. Though this was done under the premise of direct action, it was just to strengthen the demand for Pakistan. Gandhi refrained and he always left the door open for dialogue.

We can come across many such extraordinary events in the history of the Indian National Congress. When Gandhi was jailed in 1923 for spearheading the non-cooperation movement, Motilal Nehru and Chittaranjan Das seized the Congress, succeeded in breaking it and created a separate faction called Swaraj Party. When Gandhi was freed in 1924, he realised the damage it had done to the party. He opposed this split and fought hard to reach a compromise.

When the Congress rejected (the factional) senior leaders and accepted Gandhi’s leadership, he brought back those senior leaders into the party’s fold. The Congress would have suffered no significant loss, had they been sent out. However, Gandhi, on his own, would never be forthcoming to break away from anyone completely.

2. Do field work

Gandhi did not make any decision solely based on his intuition or guess work. He relied on his intuition only in choosing the appropriate time and symbolism for various struggles. Everything else he learned was through direct field work. In South Africa, when he started his campaign for equal rights, he first personally met with the Indian Diaspora there through extensive travel. Only then did he formulate the strategies for the agitation.

He already had economic plans when he came to India with dreams about Indian freedom struggle. He had already written the foundation book titled ‘Hind Swaraj’ and successfully tested a form of political struggle. Even then, he travelled in third class by train and met with people all over India and studied the situation. Through this, he formed a firsthand impression about India.

In his travels, Gandhi met many of the Indian spiritual leaders, from Sister Niveditha to Narayanaguru and held discussions with many intellectuals. No other Indian leader has accumulated such extensive direct field experience. To cite an example, we should compare Gandhi’s on-field activity with that of Ambedkar, who championed the cause of the scheduled castes but did not even consider meeting Narayanaguru. Even after being recognized as a ‘Mahatma’, Gandhi continued his travelling, several times on his own, often incognito.

When farmers requested him to take up the Champaran struggle he went to the village, stayed there, mingled with the people of that area and led the struggle. He was there for about one year. In similar vein in 1932 he toured Europe to obtain direct feedback on how the western public reacted to the Indian freedom struggle.

3. Road test your ideas

Gandhi never discussed things merely at the theoretical level. He introduced something that has never existed in the world thought before – non-violent struggle. He did not conceive it in the form of a complete theory; he wasn’t consumed in merely thinking about it or discussing it. He was not waiting to complete a flawless blueprint of his theory before he could proceed. On the contrary, he tried its effectiveness right from the formative stages.

Gandhi had tried his Satyagraha – struggle of truth, in 1906 in Transvaal, South Africa, when he was 37 years old – within months of conceiving the idea in his mind. All he learned from that struggle was obtained through outcomes of practical implementation. He framed all the rules, methods and precautions to be taken from the analysis of the outcomes. He never tried to define it in the theoretical plane without any reference to reality.

4. Start in a small way

Gandhi never started anything big just out of the blue. He had tried all struggles first in small units and implemented them extensively, only after observing its drawbacks, weaknesses and correcting them. The Non-cooperation Movement, the Salt Satyagraha, etc. came about only in this manner.

5. Correct the mistakes

Gandhi, throughout his political career, never hesitated to correct his mistakes. He did not hesitate to review his beliefs or to stop what he had been doing, because of his ego or to merely retain his image or due to overconfidence.

We can quote two examples: One was that Gandhi studied the Indian society from the perspective of a Western scholar and concluded that the caste system has a contribution to make towards the society, in a socio-economic context. But, he realized the reality of it through Congress’ activities and he changed his ideological stand completely after the discussions he had with Narayanaguru and Ambedkar, who strongly put forth those realities. He realized that whatever be the place of caste system in the society, inequalities cannot be stripped out of it hence it would be against Ahimsa. He aligned his personal life and activities in sync with these realities.

This caused a lot of conflict and confusion among some of his followers. Attempts were made on his life and he faced extreme hardships in his political life. Nevertheless he thought that the destruction that might result from correcting mistakes would be much less than the destruction if the mistakes were allowed to continue.

In a similar vein, when the non-cooperation movement he spearheaded turned violent and the police station in Chowri Chowra was attacked, he withdrew the agitation immediately even though the protest was at its peak. He thought that the Indian civil society was not yet ready for such non-violent struggle. He also realized that the Indian public should not be led directly into agitations.

No one expected that he would withdraw the non-violent struggle so abruptly. Those who were very eagerly awaiting independence were greatly disappointed and demoralised. This earned him the wrath of most of the Congressmen, including Nehru. Even today, some accuse Gandhi of backtracking and not letting people’s struggles to run its course.

But, for Gandhi, when there is a fundamental flaw, proceeding further was akin to committing suicide. He could not keep going just for the sake of it. First he enrolled thousands of volunteers into Congress, trained them properly and established a structure to manage them. With their help he took the non-violent struggle to the next level.

6. Stay in touch

Gandhi led a giant institution that had millions of members spread throughout the subcontinent. In his days, it would take as much as fifteen days to travel from one end of the country to another. A letter could even take a month to reach and get replied. He created a management hierarchy to properly manage such a setup. It was a pyramid structure consisting of village committees, district committees, State committees and the Central Committee.

Gandhi, who was at the helm of the Congress, had direct contacts even with its ordinary members. The letters he wrote were still being discovered, even after half a century after his death. He was always getting to know about various incidents that happened throughout India, directly from those involved in it. Nobody had complete knowledge about the extent of contacts he maintained.

Gandhi, who was living in North India, frequently wrote letters to Dr. MV Naidu in Nagercoil, the southernmost part of India.

7. Consult the experts

Under no circumstance did Gandhi take any decision unilaterally. Even for a less significant issue he had consultations with the experts of the relevant field. To cite an example, when the Champaran Satyagraha was in progress, Gandhi went to Ahmedabad, stayed there for a week and held consultations with various legal experts on the legal complications of the struggle. In all his great mass struggles, Gandhi always obtained the opinion of the Western political correspondents.

8. Propagandise

The senior Baniya had excellent grasp of the important aspect of the twentieth century trade. Some even call Gandhi a marketing expert. He had to mobilize millions of men and his struggle was largely built upon propaganda. There is no other political leader who did that propaganda as successfully as Gandhi.

Gandhi was constantly communicating to the millions, what he wanted to convey, with utmost clarity. His style was very simple. M. Govindan once said that Gandhi was a highly skilled pioneer among the Indian journalists. Gandhi pioneered many things, including the current style of Indian journalism. He wrote untiringly throughout his life. Today, we are astonished to see his works running into volumes. He had written all this in between his routine political tasks. He was continuously and tirelessly talking to India!

9. Let the symbols speak

Gandhi always created powerful symbols for his struggle. He knew that symbols would be more powerful than words, to reach the public. Charka was one such powerful symbol. His symbols were many – his loin cloth, the toilet, salt, etc.

For example, in 1915, when Gandhi first participated in the Congress conference, he was dressed in an Indian Shirt and a turban, like any Gujarati farmer. He stood out among the Congress leaders who were clad in Western attire. The wearied crowd suddenly took notice of him and started to listen.

There was this dramatic gesture even when he announced his struggles, Boycott of Foreign Cloths or Salt Satyagraha. When he landed in London with a goat, went on to meet the Queen of Britain clad in his loin cloth, all his actions clearly conveyed to everyone what he intended.

10. Protest only when it is unavoidable

This is an important aspect of Gandhi’s struggle. Most of his colleagues did not understand this. He always acted calmly with the understanding that the opposition was merely another side in the contest. He never considered them as enemies. This made him open to understand their good intentions and wherever possible, he even agreed with them. He protested strongly only when it was inevitable.

Gandhi had great trust in the British judicial system. He deeply revered their journalism and the democratic quality. He approached them only as his friendly force. He cooperated with the British establishment wherever it was beneficial. He did not put forth an aggressive struggle.

Whatever be the issue, Gandhi tried to achieve only those rights that the British law permitted. Then he looked beyond for further possible leverages. If necessary, he advocated a protest. He never wasted the power of struggle for the sake of sheer obstinacy.

11. Remember there is always room for compromise

Gandhi saw every struggle as a journey towards a compromise – for him, there was no struggle that ended in ‘ultimate victory’. A victory is almost impossible, where the enemies or the opponents are completely destroyed. Our opponents too have their own existence and justifications. They too will have ambitions and plans. Any decision that accommodates those too would be the only solution.

Thus, a struggle is only an action where our ideologies are summarized, our power is completely revealed and our demands are put forth. As soon as our opponents realize that we cannot be ignored, compromise is sought. In a compromise we should respect our opponents’ views as they respect ours. Compromise is a solution where both the sides gain something and sacrifice something.

Gandhi was extremely stubborn about policies that he considered close to his heart, but was always willing for any dialogue and compromise. He was always ready to concede and compromise. At the peak of the Salt Satyagraha, he accepted the compromise through the Gandhi-Irwin Pact. Through this he compensated the losses to his side, combined his strengths and sat before the dialogue table. During the peak of all struggles Gandhi always tried for compromise.

The later Marxist scholar Antonio Gramsci, calls this struggle a ‘static war’. It is retaining the gains achieved through compromise after struggle, establishing oneself in that plane and then moving on to the next stage of the struggle. At this stage, the gains achieved through compromise during a struggle, gives the energy required for the struggle.

12. Concentrate on small things

Gandhi had directed a great movement and it is only natural that he had to handle huge sums of money. Though he was always involved in big struggles, he concentrated on less significant matters too. He feared that, when millions of people were involved in an activity, a small mistake committed by one person could turn out to be a catastrophe, if it was followed by many.

To cite an example, when Gandhi attended the national conference of the Indian National Congress, for the first time in 1915, it was the lack of hygiene that first grabbed his attention. The kitchen was a mess and the toilets were stinking. His attention primarily got focused on this.

Until the end Gandhi maintained proper accounts for all sundry expenses. He expected the same from others. He wanted even the ordinary Congress volunteer to maintain proper accounts for each and every paisa. This practice of Gandhi vexed Rajaji as much that he threw the account ledgers in front of him out of frustration and left saying, “Mahatmas can be worshipped, but you cannot work with them.” But Gandhi considered a single paisa to be the basic unit of many million rupees.

He always tried to minimize the expenses by recycling old paper, building huts with locally available materials and the like. He always tried to find out the most economical way of doing things.

13. Let it settle down

One of Gandhian methods is to let the problems lose their intensity. More often when we start to recognize a problem it would already be manifesting at its peak, ready to explode. All the factions involved would be in an intensely volatile state. Any attempt at reaching a solution would identify the effort with one or the other factions. We ourselves would react to the emotional turmoil of that problem and lose our composure and the ability to analyse it.

It is akin to handling a molten lava or like trying to untie the core knot of a tangled mess while it is being pulled in four different directions.

The best way to tackle something like this is to put on hold any action and wait until the intensity subsides. Most of the issues, when postponed, would not result in heavy loss. At that stage we can wait till it naturally gets past the climax, loses the intensity and the knot starts to loosen.

What Gandhi is not suggesting is not ignoring the problem or engaging in some other activity. He advocates keen observation of the problem from outside, without any emotional involvement and remain alert about its outcome.

There are two examples. Lured by the positions offered by the British government, Motilal Nehru and Chittaranjan Das decided to break the Congress. But compromises did not work. At that stage, Gandhi distanced himself and involved himself in village development activities. For nearly five year – from 1923 to 1928 – he waited patiently. But, he was keenly observing the situation and just retained his control over the Congress.

Within four years, that dissidence almost vanished. Senior members, who were obsessed with positions, were gradually sidelined. The youth enrolled by Gandhi, including Jawaharlal Nehru, son of Motilal Nehru, made the older generation obsolete. In 1928, when Gandhi returned to lead the Congress, there was no trace of that dissidence to be found.

In 1928, the extremists within the Congress thought the time had ripened for India to launch direct confrontation for freedom. The extremist activities of Bhagat Singh and the like reached its peak. Within the party, Subhas Chandra Bose and others wanted direct action. But Gandhi held the view that India was not yet ready. He did not want to provoke the people against the armed might of the British Empire.

So, he let the situation to cool down. He requested that any such activity be put on hold for two years and the extremist faction agreed for this. Within a year it became apparent that the Indian uprising, which the extremists believed would emerge, turned out to be just an emotional outburst among the urban, literate middle class. And Gandhi moved on to Salt Satyagraha, his next stage of the struggle.

14. Accept temporary defeats

Gandhi’s struggles have faced severe setbacks at times. The outcome of any action would not just depend on the action itself, but many factors would determine it. Any single incident is only a part of the great course of history, laws of which, whether visible or not, would be constantly acting upon it. This applies to any action.

Gandhi took setbacks as a natural possible outcome. He used them to review his methods and to rethink about new possibilities. Under no circumstance did he embark on any activity with the belief that something will definitely be successful. He thought that successes and failures are beyond our grasp. But he started working with confidence on his planned action with all dedication. When the outcome was negative, he took it as just another possible outcome of that action.

The greatest of the failures of Gandhi’s struggles was the Khilafat Movement. After the first freedom struggle, viz., The Sepoy Mutiny, the British rule had the upper class Muslims under its protection. It gave them concession of twin voting right and nurtured them by giving positions in state governments. Gandhi thought that Khilafat would help to unite the humble Muslims against them and unite them with the Hindu commoners.

The Khilafat moment kindled many historic reminiscences. It attached itself to the Islamic fundamental nationalist metaphors that were emerging throughout the world. But Gandhi was not deterred by the failure and he did not abandon his objectives.

15. Fight till the end

The ultimate Gandhian rule would be this – do not give up your ideals until the end. After fixing a target, Gandhi would start moving towards that. Whatever obstacle may come, whatever setback to be faced, he will achieve the taget. Gandhi said, ‘if honest objective and the path of Ahimsa meet, success will definitely follow.’

As early as 1915, when he left for India, total independence was in Gandhi’s mind. He had presented the draft for the same in his book ‘Hindu Swaraj’, even before he came back to India. It figured in his first speech in the Congress Conference. But slowly he formulated his methods of confrontation and corrected the defects in them.

Many unexpected obstacles emerged in the course of history which Gandhi had not anticipated. One such thing was the ‘divide-and-rule’ tactics of the British. It was more successful than he had expected. The Muslims started seeking a separate nation. Throughout India many such separatist attitudes emerged, but he persisted towards his target. Had he lived longer, he would definitely have attained Gram Swaraj.

16. Realize that honesty has a trade value

Most of us believe that trade is synonymous with cunning. A cunning fellow will appear so to others and hence others would not believe him. They will deal with him with utmost cunningness and caution. This will make him spend the rest of his life acting with more and more cunningness, which in turn will make his life tougher.

A honest person earns the trust of everyone and even his enemies start trusting him. His path becomes simple. Gandhi had this favourable aspect till the end. In his early days as a lawyer, he had employed honesty as a strong weapon. He straightaway approached the opposite parties, confronted them with his honesty and won several cases.

Almost all the Viceroys, who were Gandhi’s political foes, had great respect for Gandhi’s honesty. This is evident from their writings. Especially, Lord Reading, Lord Irwin and others had a deep reverence for Gandhi. This trust opened up a royal path for him.

17. Listen to your intuitions

Gandhi always listened to his soul’s voice. His intuition guided him in his Satyagrahas. To him intuition was not God’s spiritual message. In 1929, when Gandhi intended to start a major struggle, he analyzed it from several angles and modalities. Finally, in a soporific state, he arrived at the decision as the voice of his inner soul.

It is pertinent to note that he did not heed to any wayward voice. He analyzed the struggle from multiple perspectives. He himself in the core of the issue and was engulfed by it. It is under these circumstances that he heard his inner voice. We can call this the revelation of his subconscious – when the mind converges on a specific issue, the subconscious absorbs its essence.

Most of the scientific discoveries, artifacts, philosophical theories were discovered by this process. Intuition by far outstrips logic. It takes us much further than our logical mind. Many scientific discoveries have directly been visualized in dreams by the discoverer. We see in Einstein’s life that time and again his subconscious had opened up suddenly leading to many discoveries.

A discovery or a new wisdom had always opened up and revealed itself suddenly. But a non-thinker never finds real discoveries. Only on reaching the summit of logical thinking can the inner psyche beyond that be experienced.

Similarly, it would be wrong to consider something that is attained through intuition, as the voice of God and implement it in totality. Gandhi got the idea of Salt Satyagraha as the voice of his soul. But he carefully tested it within a small area, as a sample study, and only later did he announce it at the national level.

Thomas Weber’s book ‘The Salt March : The Historiography of Gandhi’s March to Dandi’ depicts how Gandhi carried forward his great agitation. Gandhi started at a micro level, like a river springing out. Weber says, “the lean, 61 year old Mahatma holding a bamboo stick, stepped out of his ashram to protest against the world’s greatest power.”

As Gandhi continued to walk from the Sabarmati Ashram, the crowd gathered behind him and gradually swelled in number. Beyond doubt he was exploring the possibilities. He continuously assessed the occurrences and devised his strategies accordingly. Only after the concept proved to be a fool-proof one, was the Salt Satyagraha proclaimed throughout India.

In Sanskrit, trade means spreading out. Commerce is nothing but spreading out. In that sense our entire worldly life can be considered a trade. The rules of trade fit into all walks of life. So, the senior baniya can be a great guide for all your chores.

4

Was Gandhi an average Baniya? Today, some people claim that he was merely a Baniya and nothing more. To what degree is this true?

Gandhi called himself a ‘Sanatani’, in the sense that he was practising whatever best that his tradition gave him. Nonetheless when we observe his life, we can find that he never yielded to tradition. Even at an young age, he ate meat believing his friend’s words that eating meat would make him physically stronger. This only show his attitude of breaking away from tradition.

An ordinary person is one who would accept everything his tradition has to offer, as is. Caste for him is an unalterable identity and its orthodox practices would dictate the course of his life. Today we have learned not to make any reference to castes in public conversations and addresses, though we are always conscious about other’s caste. In Gandhi’s days this diplomacy was not needed.

All the same, Gandhi, throughout his life, was against the caste and the religious identity that his tradition bestowed upon him. Never for a moment did he accept caste in the context referred in the traditional sense and he never accepted the inequalities that arose from it.

In the early days of formulating his own life, he did something which, even today, an average Indian wouldn’t imagine doing. He united people of all castes, including the Dalits, to live as one family. And in that commune, he ensured that all the chores, including toilet cleaning, were carried out equally by everyone, including his own family members.

Likewise, Gandhi had not accepted his religious identity exactly as it had been. Though the practice of his religion was a combination of worship of Modh Devi, his family deity, Jainism and Vaishnavism, he never worshipped his family deity. Nor did he follow many of the rigid Jain practices. For example, consuming honey and milk and dining at night were strictly prohibited for the Jains but he was fond of these.

In a broader context Gandhi, in his later years, can be considered a Vaishnavite. However he was never interested in idol worship and he considered temples to be dirty, congested and disgusting places. Gandhi was not attracted to his contemporary Hindu seers, heads of religious institutions and spiritual sages. He never wanted to meet monks who had no interest in social reforms.

Only once did Gandhi, a Vaishnavite, visit Brindavan and when he did he felt disgusted. He had no interest whatsoever in Vaishnava Puranas and he made no efforts to read them. He never lent his ears to listen to the Bhagavatham. Nor did Krishna Leela songs, the very identity of Vaishnavism, attract him. Gandhi had no direct or indirect contact with any of the Vaishnavite religious institutions of those days.

The main reason for this detachment, as he himself said, is that his mind was not that of a traditional Indian. If it was, he would not have felt disgusted on seeing the Ganges. He would not have cringed in revulsion at the Kasi Viswanath Temple. To an Indian mind they are symbols of a great tradition. The traditional self-identity prevailing within him would have felt proud. On the banks of the river Ganga, his mind would have attained the same bliss as Vivekananda or Subash Chandra Bose had.

This was because his mind had been shaped by modern Europe and it is no wonder that during his travels within India, all he could see was filth. Even today, a European visiting India feels the same. Throughout his life, Gandhi saw all Indian traditions only through the eyes of an average European.

The nature of this land made him happy but the ruins and the antiquity did not kindle any dreams in him.

This made him appealing to all the Europeans who met him. They felt very close and familiar with him. They did not feel similar intimacy with either Nehru or Subas Chandra Bose. They did not have any limitation in understanding Gandhi, who did not follow the European logic.

Secondly, Gandhi would accept anything only after an objective and logical study, a typical European approach. Hence, he considered that caste and religion are to subjected to probe and analysis and not to be accepted unquestioned. He could not accept Vaishnavism in the form that was given to him by his family. He analysed it in his own way before accepting any of it.

His initial acceptance of caste itself can be attributed to his European attitude, where an Indian mind would either shun caste just because a European had said so or do it just to impress the Eurpoean. Gandhi, with his European empirical approach, believed that caste could be an advantageous setup. Later realising on his own that inequalities in caste system could never be obliterated from it, he took a volte-face.

We should say that Gandhi fashioned his own Vaishnavism. It is based almost entirely on the book, Gita. To him, Krishna was merely a teacher of wisdom, who authored that book. He explained the Gita in his own way to suit his own Vaishnavism. He named his commentary on Gita as ‘Anasakthi Yoga’, the yoga of non-attachment. One could say that he took the principle of Karma Yoga alone from the Gita and developed it into his own religion.

He even altered the traditional bhajans to suit him. The appended the line ‘Iswar Allah Tero Nam’ in the song ‘Ragupathi Raghava Rajaram’. This stands testimony to the compromising nature of his own brand of Vaishnavism. Gandhi put forth spinning of the charka, as a reverential prayer (Upasana). In his concept of Bhakti there is no place for rituals and practices, rather he believed that Bhakti should be expressed only by way of service.

Gandhi recognized only the service to mankind, whom he called ‘Naranarayanas’, as service to god. He did not consider any other type of Krishna Bhakti as worthy. This explains why no Indian Vaishnavite institution took note of him, though he was speaking about the Gita all through his life.

The similarity of the Vaishnavism that Gandhi created for himself with that of the religion of Kabir is noteworthy. Kabir too was involved in weaving, as Gandhi was in spinning. Kabir also tried to create a compromising faith from the best of Hinduism and Islam. Both worshipped a formless God and considered service as the only expression of Bhakti.

On the whole, Gandhi did not follow his traditional religion. He created his own religion. Likewise, he did not take or granted any of his traditional identities. He had keenly analysed the caste identity. Later, he categorically announced himself a Sudra. He proclaimed that in this era, everyone should become a toiling Sudra. He practiced it in his day-to-day life. Gandhi ensured that not a single day passed without manual labour.

At no point in his entire lifetime did Gandhi consider or express himself as a Baniya (in the traditional sense). He was never a leader of the Baniyas nor did he take up their cause. Throughout his political life he remained a leader of millions of Indians belonging to more than three thousand castes. He championed their cause.

Often it was the leaders, who lobbied only for their caste, which they were born into, who in the heart of hearts could not shed their caste identity and who could not gain the confidence of people belonging to other castes, who called Gandhi a Baniya. Gandhi was born a Baniya and lived as the only leader of India.

But the adorable aspects of the Baniya tradition were deep-rooted in him. They were the assets, traditionally handed over to him – Ahimsa and the compromising attitude of Jain tradition, the patience of the caste that united this nation for several thousand years and the down to earth approach. Our independence and the democracy that we still enjoy are the fruits of the qualities of that soul.

Jeyamohan

From the Tamil book InRaia Gandhi (Gandhi Today)

Translated by Srinivasan