One

Throughout history, the gurukula model of education was the ideal means of learning all over the world. The word gurukula refers to a lineage model of learning, where knowledge is passed on from teacher to student through generations, constituting a ‘school’ of learning over time. In Eastern countries, particularly in eastern spiritual traditions, the gurukula model was refined to the highest degree possible. The Indian tradition lists Mata, Pita, Guru, Daivam as subjects worthy of reverence – the guru is situated one step before the Lord, ahead of one’s mother and father. That is, the guru is the greatest possible manifestation of the human being. The popular hymn identifies the guru with Brahma, Vishnu and Mahadeva (Guru Brahma, Guru Vishnu, Guru Devo Maheshvara) – the guru is the same as the three gods of creation, sustenance and destruction. We see the same great place being accorded to the guru in the Zen tradition as well. Most of the popular Zen stories are about the guru-disciple relationship.

It is common to trace the roots of the schooling system to the ancient Vedic centre of learning, the patasala. However it is to be noted that the foremost god of the ancient Tamil civilisation was none other than the guru – the Great South-Facing One, Dakshinamoorthy. The teacher who teaches the student sitting at the foot of a tree was immortalised as the lord imparting knowledge at the great banyan.

The gurukula is a completely different system from a patasala. The names point out the difference. One is a kula – a house. The other is a sala – a common place. The gurukula model involves living together with the guru. The student not only learns to see like the guru, but also be like him.

In a patasala, students sit together in a group and train at the same thing, at the same standard, usually in a formulaic manner. Such formulaic learning is different from knowledge. There is no room in a Vedic patasala for original thought or critical inquiry. The ritualistic basis of enunciating the Vedas – the pronunciation, the gestures, even the manner of sitting – are all completely worked out. There is no room for change. It is the same for all. Much later, in the Buddhist viharas, similar techniques were devised to impart training in the Buddhist canon for monks. The Jaina monks who took learning to the general populace had systems similar to our present day schools, whose common name in Tamil, paLLi, is derived directly from the Jaina term, the samaNa-paLLi.

The good thing about the modern schooling system is that it provides a standard level of education for all. There is no question that this is the only way to achieve an equitable society, where everyone has access to the same kind of learning. The primary goal of the modern education system is to build up our society. A uniform society needs to have shared values, certain basic beliefs and common modes of interpersonal and societal behavior – modern education tries to ensure that this training is universally provided. On that basis, there is no doubt that our present educational system is effective indeed.

The present day educational system is democratic in nature. Standardized education and democracy are inseparable. There is something that we all know deep in our hearts – the first time we get a sense that every single person in the Indian society is considered equal, is when we enter school. Equality in an Indian village can perhaps exist only in the classroom. It is the earliest line of defence we have against untouchability, caste and economic differences that plague the rest of society. Historically, the first calls for equality and human rights, the first voices of protest, emerged in our classrooms, in states where basic education had already become widespread. Only in such regions was equitable social growth possible.

However, as an educational system, it has some basic flaws. It is meant for all, and focusses on broad abilities; the special abilities of individuals are seldom catered to. Individualistic talents are oftentimes flattened under the juggernaut of a system designed for the average Indian student. The syllabus is designed keeping all the students in mind; a student with a distinctive quest of her own is often left dissatisfied. If we consider education to be a process by which man pursues his quest for knowledge, there is not much that the present day educational system can do for him.

I say this from my own experience. I feel like I have wasted almost sixteen years of my life in regimented education. I have retained nothing from school. Everything I know, I learned outside the classroom, in the pursuit of my own questions. Even if I take a largely generous view of things, there are very few things that school taught me. An elementary familiarity with language. Social skills to mingle with society at large. But that is all. That is to say, school made me a social animal. It gave me the minimal skills required to function in society. I developed my individuality on my own, outside school.

I hated school when I was a child. The training towards becoming socially well adjusted came into direct conflict with the development of my individual self. I resisted it with all my might. The system retaliated with punishment. There were very few teachers who did not hate me. Very few classes where I did not get thrashed. I had teachers who grabbed and tore at my library books, threw it away. Once, my father whipped me all the way home from the library. When I was in the eighth class, when my first story was published in the magazine ‘Ratnabala’, one of my teachers slapped me, pulled off my shirt and made me stand up on the bench. I see that my son is alienated the same way today. “You have to cross this phase, no other way,” I tell him.

But I had a few good teachers in school. The first teacher who comes to my mind is Mr. Sathiyanesan, my Tamil teacher, who instilled a love for literature in me and taught me to write seyyul-verse. The next significant teacher I had was Sundara Ramasamy. Through him, I got introduced to Atoor Ravi Varma. Finally, I reached Nitya Chaitanya Yati. It is from them, I learnt. Where they resided, those were my gurukulas.

What is the difference between the school system and such gurukulas? The cardinal difference is this. In a school, there are lessons, but no teacher. The teacher is only a voice transmitting the lessons. There is no direct correspondence between the teacher and student in a school. The teacher is but a voice for the student. For the teacher, the student is a face, or simply a number. That is why, many times, a schoolteacher does not remember most of her students. The students, too, do not have a high opinion of the teacher. The whole enterprise of school education thus has this facade of a farce. The very knowledge the teacher purports to impart becomes an estranging rift, an obscuring veil, between the teacher and the student. The distance between our mathematics teacher and ourselves is mathematics itself.

In the gurukula model, the teacher and student have a personal correspondence with each other. This is the greatest of all the most intimate, most ardent relationships that two souls on this earth can form with each other. The knowledge they seek is the bond that holds them fast, inseparable. No ordinary mortal attachment can compare to the infinite love that grows in a student’s mind for his teacher. I have thought about my teachers endlessly, for days together. Even now, not a day passes when I don’t think of them. Whether love evolves out of the quest for knowledge, or whether knowledge becomes so dear because of love, that is a mystery.

The teacher is present in front of the student’s eyes, as a robust personality, a precedent. He shares his own self wholly with the student; verily, he is that which the student seeks to grow into. His whole future stands in front of him in human form. Imagine the rapture this induces in a young mind. Future! Fate! What else is it, but god itself? And the teacher, he is god’s other half. For the teacher, the student is his own future. Through the student, he crosses the oceans of time, he lives on. In the student is imprinted is own immortality. It is from such mutual love that true knowledge can arise. Love is the only medium that has the inherent capacity to reveal knowledge.

What is the difference between a professional teacher and a guru? “I was thinking of you all day long,” – my gurus have said these words to me many times. “Of late, my thought process has taken the form of dialogues with you,” said Sundara Ramasamy once. If I did not talk for a day, if I missed calling on them twice in a row, my teachers grieved. They became angry. Such an education is made to our measure. Watchful, compassionate love goes into its making. It is crafted with particular appeal to our tastes, our abilities and our quests, served with tender affection. There is no compare. Every moment of such an education fills us with great joy, great bliss. Not for a moment do we feel even a spot of tiredness or boredom in this school. The true pursuit of knowledge is one of the greatest delights afforded to man on this earth.

All relationships are double-edged. In my relationships with my teachers, there were also periods of extreme agony. The conflict, the grief was as intense as the love. Why did Yamunacharya try to kill his student, Ramanuja? Such great bitterness sometimes reveals itself to us in stories of teachers and disciples.There are tales of such agonized conflicts between Gaudapada and Sankara, even Totapuri and Ramakrishna Paramahamsa. It is impossible to understand this without context of the guru-disciple relationship. For me, a relationship without agon and bitterness was possible only with Nitya.

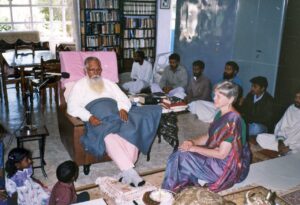

Books teach us. An author does not disappear when he dies; his words have no death. However these is a great chasm between books and men. Books impart thoughts. Teachers impart the act of thinking. Once I asked Nitya, “What do you teach your students here?” “I allow them to live with me,” he said. They walk with him, they sit with him, they eat with him and they work with him, and thus they know him. His self is his wisdom. If one is truly wise, then his wisdom will be no different from his being.

I recall now the long conversations I have had with Sundara Ramasamy, Atoor Ravivarma, and Nitya. It was not simply facts or ideas that I learned from those conversations, but how they came to it, how they recalled it. How they arranged them to arrive at a new idea. How they examined the new idea, how they took its measure. I was fascinated by how thought took sprout from thought, by the beauty of logic landing sharp and glancing off ideas, and tried to follow it myself. There were days when their language, their expressions and their gestures took possession of my tongue and body. Sundara Ramasamy had the habit of writing in the air when he worked out his thoughts. I was amused when I realised I was unconsciously doing the same thing myself.

Institutions cannot teach thinking. Only individual human beings can. That is why even institutes of higher education have created systems to foster individual guru-student relationships. That is certainly the case in academia – but it is a different question whether the spirit of the relationship is realized. That is because as I said earlier, only one human being can teach another how to think. This is because there are no limitations or structure to thinking. It is not bound by time and space. One cannot teach a student how to think between the hours of ten and eleven every day. When Nitya Chaitanya Yati was a professor at the universities of Boston and Hawaii, he scheduled his classes at the crack of dawn. There is only one way for a student to learn to think – to stay with the teacher at all times. To sit beside him, to observe his anger and joy and elation and distress up close. It is in this spirit that the Upanishad was named – it literally means “sitting close by”.

There is another thing. All thought is a response to something. The act of thinking is a search, a quest. Therefore, it can be an endless roam if we foray through books. With a guru, we get to go on a journey. We travel where he goes. We share in his hesitations and insights and thrills. The famous introductory hymn from the Kathopanishad is still sung by gurus and disciples in gurukulas all over the world. “Om, sahanavavatu sahanau bhunaktu sahaveeryam karavaavahai” “Come, let us embark on a quest for wisdom together,” the guru calls out to the disciple.

It is through the guru-disciple relationship that a school of thought stands through time. The evolution in such traditions over time can also take place only if the guru-disciple relationship is intact. All the major schools of thought in India have evolved only through the sustenance of the guru-disciple lineage. A school of thought could get ossified into a structure if transmitted through the general education system. But a worthy student not only inherits knowledge from his guru, but also ponders over it, and makes it answer his own questions. In him, it evolves to the next stage. Through a successive line of dedicated students, it sustains in time. This mode of learning is still indispensable in keeping philosophical traditions alive and relevant.

Two

Narayana Guru’s philosophical tradition is an example of a lineage of gurus and disciples in contemporary India, it is in its fourth generation today. Narayana Guru and Ramalinga Vallalar can both said to be contributions of the Tamil Siddha tradition to the modernisation of India. Narayana Guru was born in 1854 in a small village called Chempazhanji in Kerala, in a toddy-distilling caste called Ezhavas. His father was Madan Asan, mother Kuttiyamma. The caste was considered untouchable in those times. Narayana Guru learned to read Tamil at a young age, and eventually learnt Hatha Yoga from Ayyavu Asan in Thiruvananthapuram. At the age of 23, he left home to become a sannyasi, a wandering monk, and travelled through Tamil Nadu. It is conjectured that he met many practitioners from the Siddha tradition in this period. It was during this time that he also acquired knowledge of the scriptural traditions that later made him the foremost scholar of the intelligentsia in Kerala. He had peerless knowledge of the Vedas, Upanishads, Puranas, the six Darsanas, Buddhist and Jaina traditions and the three schools of Vedanta. He possessed great command over both Tamil and Sanskrit.

Narayana Guru surfaced in 1888 in a small town called Aruvikkarai near his hometown. He founded a gurukula there. “This is an exemplary place where people can live together without differences of caste or hostilities of religion,” he inscribed at its door. This attracted the attention of the Ezhavas who were then involved in social justice movements for their own upliftment. In 1903, the Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana Sabha (SNDP) was established with Narayana Guru as its figurehead. It grew as a great institution with focus on social change, religious reform and educational upliftment. Narayana Guru was hailed as the father of Kerala’s renaissance. In 1928, Narayana Guru formed an institution called Dharma Sangam with his disciples. Its headquarters is in a town in Kerala called Varkala, on a hill called Sivagiri.

Narayana Guru authored two kinds of books. One, poetic hymns, like Subramanya Satakam, Kali Natakam, Sarada Devi Stuti etc. Two, philosophical texts with a deep vision of Vedantic wisdom, like Atmopadesa Satakam, Darsanamala, Arivu etc. Narayana Guru was a Vedanti. He extended upon Sankara’s philosophical vision of Advaita Vedanta. His philosophical achievement was bringing about a synthesis [samanvaya] of all the darsanas (philosophical viewpoints) on the basis of his singular vision.

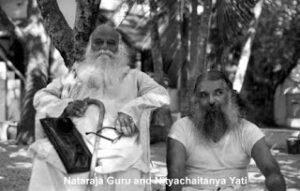

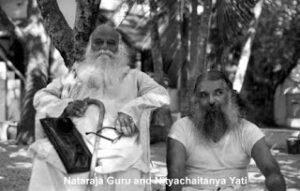

Narayana Guru had many students who contributed extensively to the building up of modern Keralite society. Many individuals who were later considered the architects of Kerala’s history held him as their idol. However, the person who can be regarded as his first disciple and spiritual successor was Nataraja Guru. He was born the son of Dr. Palpu, founder of the SNDP, in 1895. After graduating with a degree in geology, he obtained a PhD in philosophy at the Sorbonne in Paris under Henri Bergson. In 1930 he was employed to teach physics at the International Fellowship School in Geneva.

He returned to India, stayed with Narayana Guru at the gurukula, and studied the Eastern philosophical traditions under him. It is said that many of Narayana Guru’s philosophical texts were created on Nataraja Guru’s request. He worked amidst Dalits for three years in Chennai on behalf of an institution called Advaita Ashram. He wandered through Indian for six years as a mendicant. In 1923, on land received as a gift from well-wishers, he established the Narayana Gurukula at Fernhill in Ooty, erecting the first cottage with his own hands.

Nataraja Guru wrote for the most part in English and French. He was not as familiar with Malayalam. His important works include The Word of Guru, One Hundred Verses of Self-Instruction, Wisdom, Man-Woman Dialectics and The Autobiography of an Absolutist. Nataraja Guru wrote extensively about Narayana Guru in English, introducing him to a wide audience. His commentary on the Gita is considered a classic. He extended Narayana Guru’s vision of samanvaya by synthesizing it with Western philosophical traditions. As part of these efforts, Nataraja Guru travelled extensively throughout Europe. He had many students who attained great fame in later years.

Foremost among Nataraja Guru’s disciples was Nitya Chaitanya Yati. He was born Jayachandra Panikkar in 1923 in a prominent Ezhava clan in Pandhalam. His father, Pandhalam Raghava Panikkar, was a well-known poet. Nitya took up the orange robes of a sannyasi at a young age, and subsequently, lived in Gandhi’s Sabarmati Ashram and at Ramana’s gurukula. He begged his way as a mendicant and travelled through India. He obtained a Masters degree in philosophy at the SN College in Kollam, where he continued on as lecturer. He became Nataraja Guru’s student when he was employed at the Vivekananda College in Chennai. He got his doctoral degree on Bombay, with a thesis on the psychology of the blind. He was trained in Indian philosophy in Nataraja Guru’s gurukula and on his advice, in some north Indian gurukulas.

In 1969, he embarked on a world tour, starting in Australia. In the United States, at the universities in Portland, Chicago and Hawaii, he taught poetry, psychology and Indian philosophy. In 1984, he returned to India and continued the efforts initiated by Nataraja Guru. He authored 80 books in Malayalam and 150 books in English. They centre on metaphysics, western philosophy, literature, fine arts, psychology and spirituality. His commentaries on the Gita, Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, Atmopadesa Satakam and Darsanamala are considered important. Guru Nitya Chaitanya Yati passed away in 1997.

The next disciple of Nataraja Guru, Muni Narayana Prasad is the head of the Narayana Gurukula today. He has conducted extensive research into Eastern and Greek spiritual traditions and has authored more than a hundred books in this series. He lectured on Eastern philosophy in the universities at Columbo and Bali. He resides in the main gurukula (Sri Narayana Gurukula, Sivagiri, Varkala). Another disciple, Vinaya Chaitanya, is at the Somanahalli gurukula at Bengaluru. He is extensively familiar with English and Kannada literature. The students of Nitya Chaitanya Yati, including Swami Tanmaya, Swami Vyasa Prasad and Ramakrishnan are at the Ooty gurukula. Swami Tanmaya is a medical doctor in the western allopathic tradition. Today, he is well known in the field of ayurvedic research as well. These individuals represent the fourth generation of the Narayana Guru school.

Three

Very little has been written about Narayana Guru’s conversations with his disciples in the gurukulam. The memoirs of Murkoth Kunjappa, Kumaran Asan and Sahodaran Ayyappan are notable. Chidambarananda Swami has written his impressions of Nataraja Guru’s classes, just like Nitya. That book is more interesting than this, it would be a good addition to Tamil when it is translated.

This book, that Nitya Chaitanya Yati wrote in his younger days, provides a comprehensive account of life in a well-run gurukula. He was only thirty-five when he wrote this book. The seeds of the great philosophical tomes he wrote later in life are in this book. The guru and disciple travel together. The guru keeps talking. Usually in a friendly, amusing manner. Sometimes, with a flash of anger. Most of the times, he speaks as a man reflecting, with deep philosophical insight. At all times, the the two of them are in a classroom of their own, the whole universe their roof overhead.

There are three dimensions to these dialogues. One was Nataraja Guru’s daily activities, the conversations around that, his witty and philosophical utterances. Two, moments when he discusses deep philosophical ideas with others. Three, when he quotes liberally from a plethora of texts and develops his ideas. Nataraja Guru is revealed as a thinker in the course of all three activities. His insights are revealed.

Nataraja Guru’s thought process is fundamentally dialectical in nature. His calls this the Yogatma method. The Indian wisdom traditions refined this critical method thousands of years ago; Western philosophy arrived at it much later. He held that everything in nature – human emotions, thoughts, the dynamics of nature, the flow of history – all operate as a function of the interaction of opposites. This book touches on moments when he refined this process. Some sections of the book relating to philosophical investigations may sound obscure to the lay reader. In order to interpret them, it is necessary to read them in the light of discussions in Nataraja Guru’s principal texts. These sections in the context of this book are best read as an account of how a philosopher transmits such knowledge to his disciple.

Nataraja Guru holds that the goal of philosophical inquiry should be to establish the inquirer in stable, higher values, that it should ultimately be a fruitful endeavour for the seeker. Logic alone is incapable of revealing philosophical vision, he says. Philosophical insight can only be attained by intuitively resolving the dialectical contradictions in the object of study, that is, through the yogatma insight. That is beyond logic. Philosophy is thus useful only so far as it can provide a logical ground to explain intuitive insight. Insight is obtained by turning the mind inwards, and engaging in single pointed meditative focus (dhyana). It is from this perspective that he proposes his ideas.

Nitya Chaitanya Yati once reminisced about the period when he wrote this book. The book Mahendra Nath Dutta wrote about the events in Ramakrishna Paramahamsa’s gurukula had inspired him to write a similar one about his experiences with his guru, he said. However, he could not write in a sustained manner. The primary reason being, Nitya could not stop himself from engaging in a dialogue with Nataraja Guru’s ideas even as he wrote the book. Secondly, Nataraja Guru often spoke about complex philosophical theories. They were meant for advanced students, who already had a grounding in philosophical study. He wrote very little for the general reader. His methodology of teaching in the gurukula was never in the form of lectures where the students would listen in silence. They were always dialogic. The insights of his disciples were equally important in shaping the discourse. Recording one side of the conversation was incomplete and unsatisfying. Nitya had written a second draft of these conversations, but once while on a train, he had simply allowed the pages to fly out of the window. That is the reason why these memoirs are incomplete.

Despite that, I feel that this book is a testimony to how the ideals of the gurukula system are realised in practice, how the personality of a great guru engulfs and transforms his disciples. In this regard, it might serve as an inspiration for at least a few readers.

Four

I knew Prof. Jesudasan very well, and used to visit him often. He had a large, bright picture of his guru, Kottar Kumaresan Pillai, in his living room. I remember the professor recalling his guru in his conversations; even at an advanced age, there would be tears in his eyes when the name of his guru came up. When I interviewed him once, I remember how he enacted his teacher’s manner of teaching the Kamba Ramayanam with great rapture. Today, Prof. Jesudaasan’s dear students, M. Vedasagayakumar, A.Ka.Perumal and Rajamarthandan hold their place in the Tamil intelligentsia as scholars in their own right.

I know M. Vedasagayakumar for ten years now. He is, at all times, a teacher. I also consider him my teacher. I always keep learning from him about the Tamil literary tradition. I have witnessed first hand the great love and regard he always had for his teacher. Prof. Jesudasan regarded Vedasagayakumar as his own son. His love for his student can be only compared with the great affection that Vedasagayakumar holds for his own students. Sajan, Manoharan and his other students will be prominent scholars in the future.

M. Vedasagayakumar’s dear student P. Santhi has translated this difficult work carefully, with great effort. Her ceaseless motivation and attention to detail are astounding. I feel that it is only the consequence of a gurukula education. It belies a moral character that extends through generations. Santhi is working on her PhD thesis (“The influence of the Second World War on modern Tamil literature”) at the Thiruvananthapuram University College. My best wishes to her.

[Foreword to ‘Guruvum seedanum, jnanathedalin kadhai’ by Nitya Chaitanya Yati, translated into Tamil by P. Santhi, Any Indian Publications]

Translated by Suchitra Ramachandran

Related Articles