I possess a book provided by Nitya Chaidanya Yati solely for my personal study. It is a handwritten version not accessible in the public domain. While perusing it, a question arose regarding the term vyahrapada. This can be translated as pulipani in Tamil and tiger claw in English.

Vyahrapada is a sage from Hindu mythology distinguished by his tiger-like feet. Mention of this sage can be found in the Mahabharata, with his brother being Upamanyu.

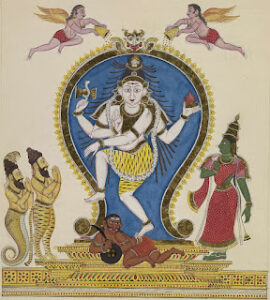

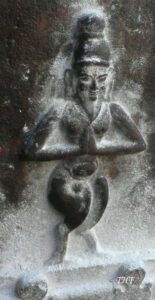

In Hindu art, Vyahrabad is portrayed as a common figure found on pillars in South Indian temples, typically depicted standing with hands joined in worship (Anjali hasta) of Shiva, appearing mostly humanoid with tiger feet.

Sage Pulipani holds significance primarily in Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Southern Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh, particularly in Dravidian sculpture. This figure is rarely encountered in North India, as the absence of ancient temples makes it challenging to ascertain its historical importance there.

According to legend, Sage Vyahrapada is credited with the construction of the renowned Vaikam Shiva Temple in Kerala. It is believed that Vyahrabada resided in Tirupattur, near Trichy in Tamil Nadu, achieving ‘samati‘ there, with a small shrine erected in his honour. He is also venerated in Chidambaram, a crucial site in Tamil Shaivism.

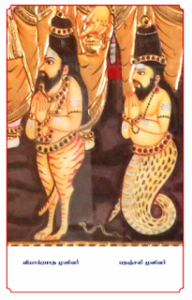

Most of the Shiva temples in Tamil Nadu feature an idol of Vyahrabada. Sage Patanjali and Sage Vyahrabada are depicted as twins in many of these temples. Sage Patanjali has a Naga body below the waist and is typically portrayed standing on the coil of his serpent body. Some temples also include Ekapada, a one-legged sage, alongside these sages.

The tale of Vyahrabada in Tamil Nadu appears to be relatively recent, serving as a children’s narrative to elucidate an unfamiliar sculpture to devout followers. According to this story, Vyahrabada was the younger brother of the sage Madhyandana and was known as Mazhan. These names are not documented in any Hindu mythology encyclopaedias.

In a quest for Kaivalya (self-fulfilment), Mazhan took on the responsibility of gathering untouched flowers to adorn Lord Shiva, seeking ones not even touched by bees. While attempting to pluck such flowers, he got pricked by thorns. Unable to climb trees, he implored Lord Shiva for assistance, and Shiva granted him the feet of a tiger, making tree-climbing effortless. By offering flowers, Mazhan achieved immortality and resided beneath Shiva in the heavenly realm of ‘Kailasa.’

In Tamil Nadu, there is a legend about a Siddha named Pulipani Siddha, who was a disciple of Sage Bhogar. They collaborated on creating the Palani Navabhashana statue. The texts attributed to Pulipani include Pulipani Vaidhyam (siddha medicine), Pulipani Jothidam (astrology), Pulipani Jalam (magic), Pulipani Vaidya Sutra (medicine), Pulipani Poojavithi (worship rules), Pulipani Shanmukha Poosai (Lord Muruga worship), Pulipani Chimizhl Vidhi (magic inks), Pulipani Sutra Gnanam, and Pulipani Sutra (Siddha Philosophy).

These texts appear relatively modern due to their language style, mainly comprising simplistic hymns with folk elements. There is uncertainty regarding their antiquity, requiring further study by scholars to determine their authenticity.

Another tale from Tamil Siddha lore recounts that during the creation of Lord Muruga’s Palani idol with toxic Navabhashana, Sage Bhogar requested water while unable to move due to poison exposure. Pulipani promptly arrived on a tiger, providing water, leading to his name derivation. Some legends associate him with a goldsmith lineage.

Pulipani Siddhar is distinct, with attempts made to merge his story with Vyahrapada from the Mahabharata, likely rooted in Bhakti and folk traditions to elucidate an unknown idol’s narrative.

Patanjali, the yoga tradition’s progenitor, shares common presence in temples with Vyahrapada, indicating their alignment within the yoga lineage.

From the 10th century AD, the yoga tradition faced challenges from the influential Bhakti tradition of South India, gradually fading into obscurity. Only remnants of this tradition endure, later interpreted by common people through their devout beliefs.

Some scholars suggest that Vyahrapada is a yogic symbol linked to the Nandinatha school of Shaiva Sidhanta, a Shaivaite tradition originating in South India. Saiva Sidhanta boasts a distinct yoga approach known as ‘Shiva yoga’, with Thirumoola as a prominent figure. The mention of Shiva as Nandi in Tirumoola’s Tirumantra holds significance.

Vaikam temple is associated with the Nandinath tradition, while many Shaiva temples represent various Shiva yoga lineages. As they transitioned to Agama worship and Bhakti practices, their yogic origins faded, surviving only in symbolic sculptures narrated through simple tales.

Delving into the interpretations and analyses of these symbols today can be a mentally strenuous task. Each person interprets them according to their own beliefs. I prefer not to engage in these scholarly debates.

Across the globe, diverse humanoid deities and symbolic images exist. While I could explore deities with tiger attributes in Egyptian and Greek mythologies, I fear such research might disrupt my inner imagery. I refrain from defining them anthropologically or placing them in historical contexts, as my pursuit is distinct.

It’s wise to retain such images in our thoughts, akin to a vine seeking support. Eventually, the essence of the universe will reach out to us. Today, I stumbled upon a revelation: “Hey, the foot of the elephant may slip, but the tiger’s foot never falters.” This left me awestruck.

During a stroll back from the bank, drenched in sweat, I pondered the significance of these lines. The tiger’s foot symbolizes versatility and strength, while the snake’s body embodies a winding path within itself.

Could this shed light on Pulipani and Patanjali? Perhaps these images serve as poetic metaphors, inviting us to introspect and integrate them into our subconscious through contemplation. Do they signify infallibility and our mind-body unity? These metaphors now hold a profound and personal meaning for me.

Jeyamohan