In the course of a recent discussion, a friend of mine referred to Sarojini Naidu’s comment on Gandhi’s simplicity being an expensive affair – with the expenses incurred to facilitate Gandhi’s travel by third class, fifty more could have travelled in first class. Incidentally, the day before, I had had a discussion with my son Ajithan, on the very same mockery concerning Gandhi’s travel by third class.

This needs a historical perspective. All our nation’s leaders of years gone by, were typically ordinary people. But, they also bore witness to the lives of Maharajas and Viceroys. They had formed the idea that officialdom was synonymous with regency. But Gandhi had bound his fellow congressmen in ties of khadi and a life of simplicity. Still, their souls craved grandeur. The leaders of Congress began nurturing dreams of becoming viceroys the moment India attained independence.

There is one thing that has been said consistently by all bureaucrats who wrote about our leaders of that era. Even until 1946, our leaders, Nehru, Patel, et al., had never dreamt that India would become totally independent or that they would be holding eminent and powerful positions. When that opportunity came, their wildest dreams rose before their eyes and glittered within their grasp. The only obstacle before them was Gandhi: the man who maintained that the Round Table Conference did not need an actual table and that it could be held sitting cross-legged on a floor, washed with cow dung. He wished that the Viceroy’s bungalow be transformed as a museum. But the leaders could now shake Gandhi off instantly.

It is now recorded history that soon after the transfer of power, Congress rulers spent hundreds of thousands of rupees to refurbish their bungalows. The first President of India, Rajendra Prasad decorated the Viceroy Bungalow further and the housekeeping employ swelled by the hundreds. He cleansed the bungalow with the holy water from the Ganges and performed grand sacred rituals of sacrifice and offerings. Sarojini, ‘the pseudo poet’, exploited the relationship between her daughter Padmaja Naidu and Nehru to obtain eminent positions for both her daughter and herself. Nehru’s entire family began enjoying the comforts and the extravagance as would befit the family of an emperor, while Vijyalakshmi Pandit had always considered herself the Empress of India.

Sarojini Naidu, while being the Governor of Uttar Pradesh, travelled to Shimla in the famed, exclusive regal train usually reserved for the Viceroys. The train was ‘a palace-on-wheels’, decked entirely in gold and silk. It was when a Keralite journalist questioned her about the prudence of this indulgence that she had made the comment on Gandhi’s travel by third class that sparked this discussion. It was the voice of Congress, trying fervently to shed the Gandhian ethics and morals. Nobody in the Congress defended Gandhi. They were in a situation where they had to justify the Shimla Trains.

In Gandhi’s time, there were nearly 450,000 full-time, salaried party workers with Congress. They were provided with a salary of just eight annas (½ a rupee) a month. They lived in sheer poverty. Advocates, wards of zamindars, graduates – all thrived on that income, travelling from place to place to enact their duties to the party. They slept on the bare ground, begging for food and travelling on foot. Most writers, thinkers and revolutionaries of modern India came from this group of workers. Premchand, Basheer, Jamnalal Patel, Tarashankar Bannerjee, Shivram Karanth, Vibhuthi Bhushan, C.S. Chellappa, all the first generation litterateurs emerged from this band of paupers. It was the sacrifice behind their simplicity that attracted the common man to Congress.

Had this culture been prevalent in Congress before the emergence of Gandhi? It was a period when legal experts and professors travelled by first class to promote the party. The Congress met annually just for the sake of a conference [in fact the very name ‘Congress’ was meant to signify a ‘Conference.’ The pioneers aimed at nothing more than organising pointless symposiums and they had no intention of transforming or promoting Congress into a mass movement.] They never dealt directly with the common man. How then did Gandhi attract hundreds of thousands of volunteers? It was his exemplary simplicity, a simplicity that the likes of Gokhale and Tilak lacked.

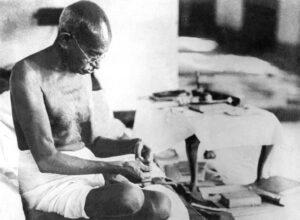

With that simple dress, that aluminium plate from which he ate, that mat he slept on and that white stone he used as a scrub, in what other class could he have travelled but by the third? Gandhi was not secretive about his simplicity. It was his proclamation. The challenges that he put forth through this proclamation were many. It stood boldly up to Kings and the Lords, with an unequivocal message that their days were over and that the era of ordinary men had begun. Gandhi conveyed this message clearly to Queen Victoria as well, calmly seated in front of the Empress at the conference table, clad in a simple, knee-length loincloth.

To this day, democracy has not found its place in the countries around us, simply because the people there could not accept ordinary men as rulers. There is, a joke about Indian President R. Venkataraman’s visit to one of the African countries, where, an African woman, on seeing Venkataraman in procession, followed by his imposing bodyguard, asks, “The President looks well and very majestic but who is that staggering old man ahead of him?” For thousands of years, in Hindu tradition, Kings have been deified as Gods. At the same time, Gods were revered in the form of rulers, personified as the kings Rama and Krishna. In a cryptic historical moment the ‘half-naked fakir’ was vested with more powers than that of a King. Because then, the people knew that the fakir was apposite. From that keen awareness, rose our undying democracy. It is but the common farmer or the woman confined to the kitchen, who understood the significance of Gandhi’s attire. In them lay the very foundation that constitutes the Indian democracy.

My grandmother, a woman with a steadfast reverence to the king, had gone to meet Gandhi when he had visited South Travancore. There, she understood that the rule of kings was coming to an end. Seeing Gandhi – recognising him to be a sage, a seer – convinced her that the rule would be of a Sanyasi from then on. This realisation led her to become a staunch supporter of Kamaraj (a former Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu), whom she considered to be a virtuous leader.

It was a period when India was in the hands of rowdy gangs of Zamindars (feudal landlords), who were in open support of the then British government. They put up a stiff opposition to Gandhi, knowing that his struggles against the powers that were, would affect them the most. It was to protect Gandhi from them, that Patel arranged to fill the third class compartment, by which Gandhi travelled, with Congress workers. Gandhi had no knowledge of these measures. This was the cost that Sarojini emphasised spitefully. “A pondering Indian would retort that the Congress was thriving only because of Gandhi’s third class travel,” declared E.M.S Namboodiripad. Congress workers would have never visited villages unconnected by railroads had Congress been led by Sarojinis and Nehrus. Sacrifice – not doctrines or dogmas – is the main force that incites social movements.

The only ones to understand this were the communists. Gandhi’s was the only portrait that E.M.S Namboodiripad had in his house. As an ardent follower, he was a true Gandhian who took to washing his own clothes. This was the kind of leadership that inspired workers to carry out the responsibilities of the party, sustaining on naught but a cup of tea. This tradition died the moment that Gandhi did. Times changed to a point where a worker would consent to hold a placard only if was to be paid for it. Why must he be fool enough to travel on foot while his leaders travel on the Viceroy train?

The other day, I saw a group of Dalits – ones who scavenge the city roads – writing graffiti (of party propaganda) on the walls in my locality, for the Communist Part. All of them had volunteered for the work. Not very far off, on adjacent walls, were the giant slogans of other parties, written with high quality, branded paints, by professional advertising companies, chosen by tenders. The cost incurred would be covered by business owners and corporate backers. The reason for the Dalits volunteering was that their leader, Member of Parliament, Advocate Bellarmine, wouldn’t have had a second’s hesitation to stand right next to them, dhoti folded around his knees, a can of tar in his hand. Some years back, I have seen for myself, the great leader, J. Hemachandran, standing with his party workers, in the wee hours of one morning, writing slogans on the walls.

Travelling by third class, loincloth-clad Gandhi was a living banner. To realise that this is the essence of democracy, you need a slightly receptive conscience and a fair grasp of history.

Jeyamohan

From the Tamil book InRaia Gandhi (Gandhi Today)

Translated by Srinivasan