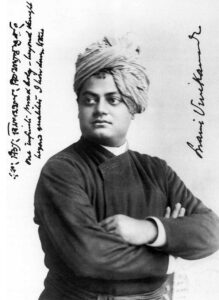

Most people’s first impression of Vivekananda comes through the calendar images they see at a very young age. It is the photograph taken by the famous American photographer Thomas Harrison in 1893. The photo, where Vivekananda stands slightly turned to the side, dressed in a saffron robe with a Bengali turban and arms crossed, exudes a sense of confidence that has resonated across five generations.

India was a country overshadowed by poverty and cowardice, shrouded in hunger. It was a nation that had lost its confidence, cowering in fear of the world. When the youth of the country looked into those eyes, they found themselves. In Vivekananda’s eyes, they saw the confidence of Indian youth standing tall against the world. That photograph became a grand image, a clarion call to the world saying, ‘Come, world!’

There are hundreds of books about Swami Vivekananda in Tamil. The book ‘Swami Vivekanandar’ written by A. L. Natarajan can be considered a comprehensive introduction. Vivekananda has been discussed from many perspectives. There are books written by Vedantists and traditionalists, as well as the words of leftists like Jayakanthan.

Everyone is inspired by his personality. In his M. O. Mathai’s autobiography, Ambedkar tells him, ‘The greatest Indian of our century is Vivekananda. The new India begins with him.’

Vivekananda was a religious reformer, social reformer, and philosopher. Above all, he was a sage. Sages are like the fingers of our hand. Everyone has been assigned a task by nature.

Accordingly, their nature is designed. Some are like the index finger, some like the thumb, and some like the little finger. Yet, all together they serve the same purpose. Therefore, if we define a sage by our limited understanding, it is our loss. Only the depths of our quest for wisdom can identify them.

India has never lacked for sages. Thousands of ascetics lived here, living off alms from the village and scraps from garbage. Among them, there might have been one whose fate was destined to turn back and look at our people, our country, our culture, and our politics. Such a person was Vivekananda, who arrived in that very manner.

The slavery that had engulfed this country and the severe famines that resulted were the reasons for his arrival. The English education provided in the country served as a tool for his purpose. The railway system that was developing at the time also became vehicles for the changes he envisioned. Vivekananda arrived and left, and this land awoke from its slumber.

This is Vivekananda’s contribution. He was the seed of the entire national self-awareness that developed in this country. The fire of spiritual awakening that emerged from Vivekananda was born from his realization of India’s decay due to degradation and superstitious thoughts. The Upanishadic line, “Arise, awake, and stop not till the goal is reached,” can be called the ‘guiding mantra’ he gave to India.

From his writings, one can discern the starting points for all modern thoughts of this country. A profound understanding of India’s landforms and geography is reflected in his writings, which was his first gift to India. From Badrinath to Kanyakumari, he traveled in the opposite direction to that of Adi Shankara’s journey. The map of India was discussed at every place he visited throughout his journey. The dream of a ‘New India’ began to take shape through this, as can be seen in the notes written by those who met him, such as Rajam Iyer.

At that time, the Indian spiritual tradition was intertwined with religious rituals, ceremonies, and practices. Movements like the Brahmo Samaj, which sought to break away from this complexity and create something new, and organizations like the Arya Samaj, which aimed to center on a particular aspect of Indian knowledge while elevating everything around it, were present.

Vivekananda’s contribution encompassed all the essential aspects of the Indian philosophical tradition. He identified them, synthesized them comprehensively, and expressed them in a dignified language directed towards India. It can be said that the language of Indian philosophy transitioned from Sanskrit to English through him. Vedanta, once confined to monasteries and gurukuls, became a philosophy for Indian youth through his efforts.

Even today, a thinker who views the entirety of Indian thought would identify Vivekananda as their teacher. A prime example is K. Damodaran, a Marxist philosopher. For him, who attempted to frame Indian thought from a Marxist perspective, Vivekananda appeared as an immediate predecessor. It is because of him that leftists today mention Vivekananda’s name.

Vivekananda was the first voice of India’s renaissance. Like a falcon that ascends to the roof of our fallen and dilapidated house, spreads its golden wings towards the golden dawn, and calls out, he raised his voice for India. He was the first to offer thoughts on the model of Indian historical evolution, the educational system suited to India, and the concept of a popular democratic polity for India.

He has spoken about the protoforms of Indian literature and debated the fundamental forms of Indian arts. He was among the first to speak about India’s unique architecture and painting styles. For instance, many of India’s great pioneers received their initial inspiration and guidance from Vivekananda. The foundational impetus for Indian painting, for figures like Abanindranath Tagore, came from Vivekananda.

India has always been regarded as a land of wisdom. We have thought of ourselves as the land of the elderly and the ancient. He is the youth who broke that mental imprint and emerged anew. His beautiful face, with the innocence of childhood, became the symbol of a new India. Many who served this country and its people, who created revolutions here, and who created art and literature here, would have identified with Vivekananda in their youth.

The beautiful face still remains today. Fate, with great mercy, made him eternal in our memories, forever in youthful grace.

12 Jan, 2014 Tamil Hindu Daily

Translated By Geethaa Senthilkumar